INTRODUCTION

SARS-CoV-2 infection, responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, has caused more than 550 million cases and more than 6 million deaths worldwide until June 2022. This virus belongs to the family Coronaviridae. This family comprises enveloped viruses, with a positive sense genome of around 30,000 nt. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, the genome codes for four structural proteins (nucleocapsid or N, spike or S, membrane or M and envelope or E), 15 non-structural proteins and eight accessory proteins. The S protein contains two regions: S1, which includes the receptor-binding domain (RBD), and S2, with the furin-cleavage site and the fusion peptide. RBD, specifically the receptor binding motif (RBM), is the region responsible for the attachment to the angiotensinconverting enzyme 2 (ACE2) cellular receptor (Fig. 1)1,2. Two other putative receptors (Asialoglycoprotein Receptor 1 - ASGR1- and KREMEN1) have been described recently for SARS-CoV-2, which are not used by the previous SARS-CoV. The virus appears to interact with these two additional receptors through the RBD and also with N-terminal domain of the S1 region3,4. These new candidates add to the list of other potential ligands that may interact with SARS-CoV-25,6.

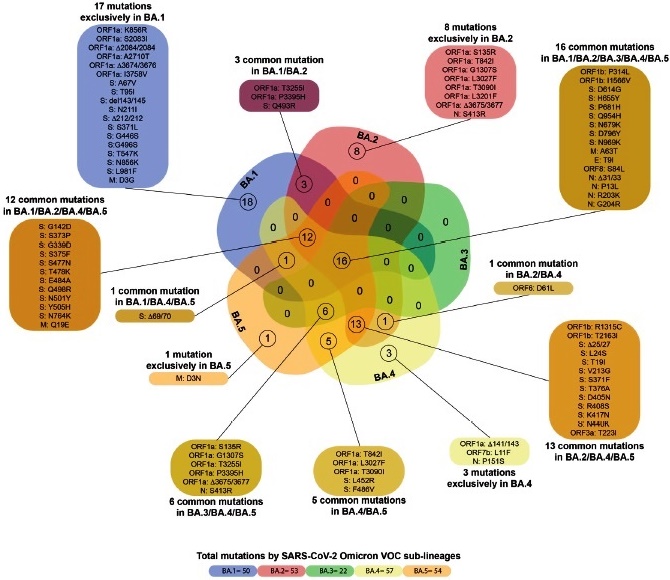

Fig. 1 Mutations of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron VOC sub-lineages. Venn diagram showing common mutations between the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron VOC sub-lineages.

During these two years of a high rate of replication, this virus has accumulated several mutations, allowing for its classification in more than 2000 lineages by June 20227-9. Some of these lineages were denominated as variants by WHO10. These variants (lineages of viruses sharing particular types of mutations) emerged since the end of 2020, and were defined as Variants Under Monitoring (VUM), Variants of Interest (VOI), and Variants of Concern (VOC), when any different phenotypic trait, such as increased transmissibility or immune evasion, among others, was suspected for the two firsts and confirmed for the last10. Until June 2022, five VOCs were described: Alpha variant, which emerged in the UK (lineage B.1.1.7), Beta variant in South Africa (B.1.351), Gamma variant in Brazil (P1), Delta variant in India (B.1.617.2), and Omicron variant, first identified in South Africa (B.1.1529). The last one was included in the list of VOCs very soon after its identification. By the end of June, only the Omicron VOC and its sub-lineages were present as a VOC10.

This variant caused immediate concern, due to the explosive increase in cases in South Africa11, and the large number of mutations exhibited by this new lineage. In this study, we describe the characteristic mutations of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2, and the behavior of the epidemic waves associated with the dissemination of the different sub-lineages throughout the world.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Description of the mutations characteristic of each sub-lineage of Omicron. The identification of characteristic mutations of the five sub-lineages of Omicron was performed using the following databases: SARS-CoV-2 lineages (Cov-lineages. org), Outbreak.info and, GISAID EpiFlu™ (https://www.gisaid.org/). The Venn diagram was made in Bioinformatics & Systems Biology UGent/VIB (bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be), and edited in Illustrator CC (ver. 23.0.1).

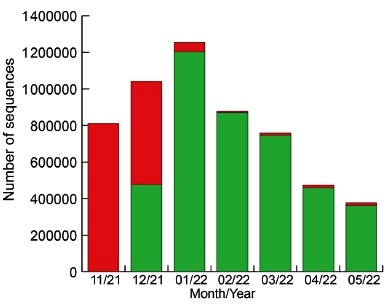

Analysis of the frequency of Omicron VOC in the world from November 2021 to May 2022. The number of sequences of Omicron VOC available at the GISAID database (https://www.gisaid.org/) on June 26, 2022 was compared to the total number of sequences foe each month, between November 2021 and May 2022.

Frequency of Omicron VOC sub-lineages in the world. The number of sequences reported for each Omicron VOC sub-lineage, together with the date of the first and peak detection, were analyzed from “SARS Cov2- Lineages.” https://cov-lineages.org/lineage_list.html9, and accessed on June 26, 2022.

Analysis of the epidemic waves caused by the Omicron VOC in different countries. The peak number of cases caused by the circulating Omicron VOC was analyzed in selected countries, and compared with the previous highest peak of cases occurring in the same country, using the Worldometer database (https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/, accessed on July 1, 2022).

RESULTS

Key mutations of the Omicron variant

The Omicron variant exhibits a large number of mutations in its genome, particularly in the S protein (Fig. 1). Five sublineages of the Omicron variant have already been identified, which exhibit some differences with the original B.1.1.529 lineage and between them (Figs. 1 and 2). Additionally, a recombinant BA.1/BA.2 sub-lineage has also been described (Table 1).

Table 1 Description of Omicron VOC sub-lineages.

| Omicron main lineage | Sub-lineages1 | Date of first detection | Date of peak detection2 | Number of sequences3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA.1 | 50 (54) | 2/9/21 | 4/1/22 | 2166293 |

| BA.2 | 53 (108) | 11/10/214 | 28/3/22 | 1625851 |

| BA.3 | 2 | 23/11/21 | 3/2/22 | 745 |

| BA.4 | 1 (4) | 10/1/22 | 25/5/22 | 13334 |

| BA.5 | 2 (15) | 5/1/22 | 30/5/22 | 27560 |

| XE5 | 1 | 19/1/22 | 28/3/22 | 2438 |

Information from 9, accessed on June 26, 2022.

1 The effective number of sub lineages is shown, with the number of proposed ones indicated under parentheses.

2Date when the highest number of sequences were available was June 26, 2022. This date may change, particularly for lineages BA.4 and BA.5, which are more actively disseminating in June 2022.

3The number of total sequences tentatively assigned to this lineage is shown.

4An earlier date of detection is reported for sub-lineage BA.2.3 (29/9/21).

5Recombinant BA.1/BA.2.

The number of mutations exhibited by the different sub-lineages of Omicron VOC ranges from 22 for BA.3 to 57 in BA.4. Key mutations of the S protein and present in almost all the sub-lineages are shown in Fig. 2. The S371L, K417N, and N440K mutations, although not present in all the BA.1 isolates, are however also frequently found, according to a search in GISAID database (data not shown) In the case of BA.3, many key mutations present in the other lineages of Omicron, such as D405N, K417N, N440K, T478K, E484A and N501Y, were found in most sequences of lineage BA.3 available in the GISAID database (data not shown).

Of particular relevance is the absence of the deletion of the amino acids 69 and 70 in the S protein in the BA.2 sub-lineage, which instead possesses a deletion of the amino acids 25 to 279 (Fig. 1). Another important mutation acquired by the BA.4 and BA.5 sub-lineages is the L452R mutation (Fig. 2), a key mutation in the Delta VOC, which was previously identified, particularly in some Californian variants. The sub-lineage BA.2.12.1 carries the mutation L452Q, previously described in the C.37 VOI9.

Omicron dissemination and sub-lineages

Soon after its emergence, the Omicron VOC displaced very rapidly the other lineages circulating in the world, mainly the Delta VOC (Fig. 3). At the end of June 2022, the Omicron VOC was the only VOC recognized by the WHO, although some Delta VOC isolates were still described in the GISAID database.

Fig. 3 Frequency of Omicron VOC around the world from November 2021 to May 2022. Green: Omicron VOC. Red: other lineages, mainly Delta VOC. From GISAID (https://www.gisaid.org/ accessed on June 26, 2022). In November 2021, only 3217 sequences of Omicron were available out of 810820 total sequences.

At the end of June 2022, the most frequent lineages found in several parts of the world were the sub-lineages BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5. These 3 lineages are expected to circulate abundantly in the next months of 2022. Very few sequences of sub-lineage BA.3 were available at GISAID database (Table 1).

Table 2 shows some representative patterns of the epidemic waves caused by the Omicron VOC and its successive sub-lineages. Generally, the Omicron VOC dissemination caused an epidemic wave of unprecedented magnitude, when compared to the previous waves. Exceptions to this are India and Iran, for which the ratio of Peak number of cases with Omicron VOC/Peak number of cases before Omicron VOC (PNO/PNBO) was below 1 (Table 2). Additionally, this ratio is highly variable between countries, being generally lower in American countries, compared to European ones, for example. The second epidemic wave of Omicron VOC, due to the dissemination of sub-lineages such as BA.2, BA.4 and BA.5, was observed earlier in many countries of Europe, while in America, for example, some countries were suffering an ongoing peak at the end of June 2022 (Table 2).

Table 2 Omicron VOC epidemic waves in selected countries.

| Country | Pop (M hab) | Cases1 (M) | PNBO2 | PNO3 | PNO /PNBO | SOP4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| America | ||||||

| USA | 334.9 | 89.4 (1) | 310,438 (8/1/21) | 908,909 (14/1/22) | 2.93 | 140,047 (23/6/22) |

| Brazil | 215.6 | 32.4 (3) | 115,041 (23/6/21) | 282,050 (3/2/22) | 2.45 | 75,106 (30/6/22) |

| Argentina | 45 | 9.4 (13) | 41,080 (27/5/21) | 139,853 (14/1/22) | 3.40 | 8,314 (26/5/22) |

| Colombia | 52 | 6.2 (18) | 33,594 (26/6/21) | 35,575 (15/1/22) | 1.06 | 3,403 (28/6(22) |

| Mexico | 131.6 | 6 (20) | 28,953 (19/8/21) | 60,552 (20/1/22) | 2.09 | 32,216 (30/6/22) |

| Chile | 19.4 | 4 (31) | 9151 (9/4/22) | 39,840 (10/2/22) | 4.35 | 13,104 (17/5/22) |

| Venezuela | 28.3 | 0.5 (86) | 1,786 (4/4/21) | 2,646 (30/1/22) | 1.48 | 199 (24/6/22) |

| Africa | ||||||

| South Africa | 60.8 | 4 (30) | 26,645 (3/7/21) | 37,875 (12/12/22) | 1.42 | 10,017 (11/5/22) |

| Asia | ||||||

| India | 1,407 | 43.5 (2) | 414,433 (6/5/21) | 347,254 (20/1/22) | 0.88 | 19118 (30/6/22) |

| South Korea | 51.3 | 18.4 (9) | 7434 (17/12/21) | 621,328 (17/3/22) | 83.58 | 10,437 (29/6/22) |

| Iran | 86.1 | 7.2 (17) | 50,228 (17/8/21) | 39,819 (7/2/22) | 0.79 | 4,615 (5/4/22) |

| Hong Kong | 7.6 | 1.2 (55) | absent | 79,876 (3/3/21) | +++ | 2,352 (30/6/22) |

| Europe | ||||||

| France | 65.6 | 31.1 (4) | 83,321 (7/11/20) | 501,635 (25/1/22) | 6.02 | 217,480 (29/3/22) |

| UK | 68.6 | 22.7 (6) | 83,088 (30/12/20) | 275,618 (5/1/22) | 3.32 | 109,320 (22/5/22) |

| Italy | 60.3 | 18.6 (7) | 41,386 (13/11/20) | 228,740 (18/1/22) | 5.53 | 100,823 (20/4/22) |

| Denmark | 5.8 | 3 (39) | 4,508 (18/2/20) | 52,009 (10/2/22) | 11.54 | 2,407 (28/6/22) |

| Oceania | ||||||

| Australia | 26.1 | 8.2 (16) | 2,528 (9/10/21) | 150,702 (13/1/22) | 59.61 | 67,379 (30/3/22) |

| New Zealand | 5 | 1.3 (53) | absent | 24,106 (2/3/22) | +++ | 8,331 (28/6/22) |

1Cases: Total number of cases in millions (M) until July 1, 2022 (position in the ranking of cases).

2PNBO: Peak number of cases before Omicron VOC (date).

3PNO: Peak number with Omicron VOC (date).

4SOP: Secondary Omicron VOC peak (date).

Several factors may have affected the analysis. The testing capacity of each country, which ranged in July 1, 2022, from five tests/million inhabitants in Algeria, to 21,890,462 tests/million inhabitants in Denmark (https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/), may have limited more accurate estimation of cases during the epidemic waves, particularly during the Omicron VOC one. With the highest testing capacity, Denmark exhibited a high PNO/PNBO of 11.54 (Table 2). The intensity of the Delta VOC epidemic wave, which was particularly high in some Asian countries, like India and Iran, led to a reduction of this ratio in these countries, probably combined with saturated testing capacities. PNO/PNBO is of particular interest in countries like South Korea (83.58), Australia (59.61) and New Zealand (unassigned since no peak in the number of cases was observed before the Omicron wave (Table 2). In Colombia and Venezuela, for example, the PNO/PNBO was close to 1 (Table 2). In addition to possible testing saturation during the Omicron VOC wave in these countries, the lower severity associated with this variant, particularly in young persons, may have reduced the demand for testing in some groups.

DISCUSSION

Soon after its identification, the Omicron variant was declared as a VOC, especially due to the huge number of mutations it harbors11. Of the more than 30 mutations present in the Omicron variant in the S protein, around half of them are located in the RBD12. Some of these mutations can be used detecting of this VOC by rapid methods13. Seven produce a modest increase in the affinity of the RBD for the ACE2 receptor: Q493R, N501Y, S371L, S373P, S375F, Q498R, and T478K12,14. It has been shown that Omicron VOC can infect murine cell lines15. At least two of the substitutions responsible for the increase in affinity for the human ACE2 receptor are also responsible for the increase in binding to mouse ACE2: Q493R and Q498R15,16. Furthermore, the molecular spectrum of Omicron-acquired mutations was significantly different from the spectrum for viruses that evolved in human patients. However, it resembles the spectra associated with virus evolution in a mouse cellular environment. These observations lead to the suggestion that the progenitor of Omicron might have jumped from humans to mice, accumulating mutations conductive to infecting that host, then jumping back into humans, indicating an interspecies evolutionary trajectory for the Omicron outbreak15. Thus, this increased propensity for reverse zoonosis makes this variant more likely than previous variants to establish an animal reservoir of SARS-CoV-2.

Recent studies show that Omicron VOC exhibit a replication enhanced in human primary nasal epithelial cells, and reduced in pulmonary cells17-20. This trait appears to be related to the fact that, unlike other SARSCoV-2 variants, Omicron is capable of efficiently entering cells in a TMPRSS2-independent manner, via the endosomal route. This enables Omicron to infect a greater number of cells in the respiratory epithelium, allowing it to be more infectious at lower exposure doses and resulting in enhanced transmissibility17. Syncytia formation depends on the fusogenic activity of the S2 region of the S protein after cleavage by the TMPRSS2. The Omicron also forms fewer syncytia than other lineages20,21. The authors suggest that this phenotypic trait may be due to the presence of the mutation N969K. The role of syncytia formation in the pathogenic effect of SARS-CoV-2 remains a matter of debate22. Other substitutions, such as N679K and H655Y, may be contributing to this particular phenotype in Omicron VOC. The N679K substitution is located in the QTQTN motif upstream of the furin cleavage site (QTQTK in the Omicron VOC). The cleavage site is known to play an important role in viral pathogenesis. Its deletion attenuates viral replication in respiratory cells in vitro and attenuates disease in vivo22. The substitution N679K in the QTQTN motif of the Omicron VOC has been shown to reduce the affinity of the protein for furin, resulting in a reduced susceptibility to serine proteases on the cell surface for entry23,24. The substitution H655Y, in contrast, has been shown to enhance viral replication and spike protein cleavage25.

One of the most striking characteristics of the Omicron VOC is its ability to evade protective immunity induced by previous infection or vaccination26,27. In fact, it is believed that the increase in transmissibility of this variant is primarily due to its ability to evade previous protective immunity rather than to of a higher affinity of its S protein for the ACE2 receptor28. Several mutations of Omicron VOC could impair neutralizing antibodies (Nabs) with different specificities. Specifically, mutations K417N, G446S, E484A, and Q493R induce escape of Nabs in Group A-D, whose epitope overlaps with the ACE2-binding motif. Group E (S309 site) and F (CR3022 site) NAbs, which often exhibit broad Sarbecovirus neutralizing activity, are still somehow effective against the Omicron VOC, but mutations G339D, N440K, and S371L may induce resistance to a subset of Nabs27.

The Omicron VOC also exhibits an insertion of 3 amino acids (EPE) in the N-terminal region of the S protein, at residue 214. This insertion of EPE has not been observed in other major variants of SARS-CoV-2 and may induce a structural change, which might be associated with a decrease in neutralizing antibody binding ability to this region. This genomic insertion has also been suggested to be incorporated into SARS-CoV-2 by recombination with another coronavirus or even other respiratory pathogens29,30. The mutation L452R present in sub-lineages BA.4 and BA.5, may confer to these Omicron VOC sub-lineages an increased immune evasion31,32, and may also contribute to the dissemination of these lineages. The sub-lineages more frequent in June 2022, BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5, exhibit an increased potential of breakthrough infection after vaccination and infection, even with a previous infection with another Omicron VOC33-35.

In contrast, the sub-lineage BA.3 of the Omicron VOC did not exhibit wide dissemination, compared to the other ones. This may be related to the absence of many key mutations exhibited by the other sub-lineages, related to increased transmissibility and immune evasion (Figs. 1and 2). However, the number of mutations found in this sublineage is also variable among different isolates, and some of those key mutations are also frequently found.

Several lines of evidence suggest that the Omicron VOC is highly more transmissible than all previous variants, in addition to the reduced sensitivity to the immune protection conferred by vaccines and previous infections. The effective and basic reproduction numbers of the Omicron variant have been estimated to be 3.8 and 2.5 times higher than that of the Delta variant, respectively, which was the previous VOC displaying the highest reproduction numbers36.

From this significant increase in transmissibility and resistance to previous immunity, it could be inferred at a first glance, that the clinical course of the Omicron VOC might be more severe. However, the changed tropism of this variant, to a virus infecting more the upper respiratory airway, compared to the lungs, suggests that is the contrary. Indeed, several studies point to a less severe clinical course of infection with the Omicron VOC, compared to the infection caused by the Delta VOC.

The first evidence comes from in vitro and animal model infections, where the Omicron VOC exhibited an attenuated phenotype37. The early studies of the Omicron VOC in South Africa also suggested a reduced odd of severity for the patients infected with this VOC38. This trend was confirmed in a retrospective observational study39. The same observation was found among US Veterans40. Children in Israel were less prone to develop multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MISC), a common sequel of COVID-19 in children, during the Omicron VOC wave, than during the Delta and Alpha VOC waves41.

The emergence of Omicron VOC and its sub-lineages led to an abrupt epidemic peak worldwide42. However, differences in the intensity of the epidemic peak caused by the Omicron VOC were however observed between countries. For example, countries such as South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand were characterized by a successful control of COVID-19 during the pandemic43-45, until the Omicron VOC wave. The increased transmission ability of the Omicron VOC allowed it to spread widely even in countries with previous highly successful control measures. Finally, the great disparities in vaccination coverage between countries46, also had a profound influence on the intensity of the Delta and Omicron VOC waves.

In conclusion, the Omicron VOC displays a great number of mutations, some of them already present in previous lineages. Although associated with a high attack rate and immune evasion, this variant seems to be associated with lower severity, compared to previous ones. A probable explanation for this somehow attenuated phenotype could be related to its resistance to the cleavage of TMPRSS2 and probably furin, and its reduced ability to form syncytia, leading to increased tropism for epithelia over the lungs. The reduced effectivity observed for various vaccines to protect against infection with this variant has not hampered its effectiveness in reducing the morbidity and mortality of COVID-19, particularly with a booster dose, which still induces neutralizing antibodies47. The well-known non-pharmacological preventive interventions (mask, social distancing, ventilation and frequent hand hygiene), together with vaccination, are still the most effective measures to reduce the burden of this highly contagious variant.

uBio

uBio