Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Archivos Latinoamericanos de Nutrición

versión impresa ISSN 0004-0622

ALAN vol.67 no.1 Caracas mar. 2017

Composición nutricional, compuestos fenólicos y capacidad antioxidante de cascarilla de garbanzo (Cicer arietinum)

Guillermo Niño Medina, Dolores Muy Rangel, Aurora de Jesús Garza Juárez, Jesús Alberto Vázquez-Rodríguez, Gerardo Méndez Zamora, Vania Urías Orona

Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Facultad de Agronomía, Nuevo León, México. Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo (CIAD), Culiacán, Sinaloa, México.

Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Facultad de Salud Pública y Nutrición. Monterrey, Nuevo León, México.

RESUMEN. La composición química, minerales, azúcares neutros, compuestos fenólicos y capacidad antioxidante fueron analizados en la cascarilla de garbanzo. La cascarilla de garbanzo presentó 72% de fibra dietaria, del cual el 24.4% fue celulosa. Los compuestos fenólicos y actividad antioxidante de la cascarilla de garbanzo fueron evidentes, predominando los taninos condensados totales con 13.28 mgEC/g, donde la fracción soluble fue mayor respecto a la fracción ligada. El contenido de proteína y grasa fue de 4.5 y 0.4%. En conclusión, la cascarilla de garbanzo tiene propiedades nutricionales y funcionales que pueden ser consideradas en el diseño de nuevos productos alimenticios para mejorar la salud de los consumidores.

Palabras clave: Composición química, fibra dietaria, azúcares neutros, compuestos fenólicos, actividad antioxidante, Cicer arietinum.

SUMMARY. Nutritional composition, phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of chickpea (Cicer arietinum) husk. The chemical composition, minerals, neutral sugars, phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity were analyzed in the chickpea husk. Chickpea husk presented 72% of dietary fiber of which 24.4% was cellulose. The content of phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of chickpea husk was evident, predominating condensed tannins with a total content of 13.28 mgECat/g, of which soluble fraction was the higher than bound fraction. The content of protein and fat was 4.5 and 0.4 %, respectively. In conclusion, chick pea husk has nutritional and functional properties that can be considered in the design of new food products to improve the health of consumers.

Key words: Chemical composition, dietary fiber, neutral sugars, phenolic compounds, antioxidant capacity, Cicer arietinum.

Recibido: 26-07-2016 Aceptado: 09-10-2016.

INTRODUCCIÓN

El consumo de leguminosas es importante, sus granos o semillas tienen más proteínas que los cereales, alto porcentaje fibra dietaria, minerales y almidón (1); además poseen efectos fisiológicos benéficos en la prevención de la diabetes, problemas de obesidad, enfermedades cardiovasculares y cáncer de colon (2). La cascarilla, pericarpio o cubierta de las leguminosas normalmente son destinadas como alimento para ganado después del procesamiento del grano. Son un material de desecho de algunas industrias alimentarias como la aceitera y harinera, representan un subproducto del 20% del total de la leguminosa procesada (3). Este tipo de industrias generan residuos con potencial antioxidante, antimicrobiano, así como compuestos bioactivos, tal es el caso de la cascarilla de garbanzo. Además de ser un sub producto de bajo costo, la cascarilla de garbanzo posee un alto contenido de fibra dietaria y polifenoles. La fibra dietaria, se constituye de celulosa, hemicelulosa, pectina, lignina, gomas y su consumo trae consigo beneficios al organismo humano como la disminución del colesterol, lipoproteínas de baja densidad (LDL), problemas del tracto digestivo e incidencia de cáncer de colon (4). Por su parte, los compuestos fenó- licos son metabolitos secundarios esenciales para el desarrollo y crecimiento de las plantas, usados como mecanismo de defensa. Los polifenoles (flavonoides, taninos, ácidos fenólicos) desde el punto vista nutricional tienen un alto impacto por su actividad antioxidante (5). Los antioxidantes reducen el estrés oxidativo y participan en la prevención de enfermedades degenerativas como el cáncer y padecimientos cardiovasculares, poseen propiedades antiinflamatorias, y su efectividad depende de la cantidad consumida y su biodisponibilidad (6). El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar la composición química, minerales, azúcares neutros, compuestos fenólicos y capacidad antioxidante de la cascarilla de garbanzo.

MATERIALES Y MÉTODOS

Obtención de la cascarilla de garbanzo

Grano de garbanzo tipo Kabuli Variedad ʽJumboʼ de coloración crema fue donado por la Unión Nacional de Productores y Exportadores de Garbanzo (UNPEG, Culiacán, Sinaloa, México). Dos muestras de 6.25 kg con dos replicas (n=4) se utilizaron para la caracterización. El grano fue humedecido en agua a 40°C durante 2 h, posteriormente la cascarilla del grano fue separada manualmente y secada durante la noche a 45°C. Finalmente, la cascarilla fue molida y tamizada a tamaño de partícula de 420 μm (malla 40), obteniendo un rendimiento de 3.5 %.

Análisis proximal y minerales

El análisis proximal y de minerales fue realizado de acuerdo a las metodologías oficiales de la AOAC (7): humedad (método 925.09), grasa (Soxhlet, método 923.03), fibra cruda (método 920.86), proteínas (micro Kjeldahl, método 960.52) y cenizas (método 923.03); el contenido de carbohidratos fue estimado por diferencia y los carbohidratos totales fueron obtenidos por diferencia más el contenido de fibra cruda. El contenido de fibra dietaria total (FDT) fue determinado basado en el método 985.29, utilizando el kit de fibra dietaria Megazyme®. En la determinación de minerales (método 955.06), las muestras fueron sometidas a una digestión ácida (HCl) y posteriormente se determinó el contenido de minerales en un espectrómetro de absorción atómica SpectrAA-220 (Varian). Los elementos de K y Na se analizaron por emisión de flama a 589.6 y 769.9 nm, respetivamente. El contenido de Ca, Mg, Zn, Cu, Fe, Mn se determinó por absorción atómica a 422.7, 285.2, 213.9, 324.7, 248.3 y 279.5nm, respectivamente.

Azúcares neutros (AN)

La determinación de AN fueron realizados por cromatografía de gases; 3 mg de cascarilla fueron tratados con 500 μL de ácido trifluoroacético 2N durante 1 h a 120°C, utilizando 200 μg de mio-inositol como estándar interno. Enseguida la muestra fue centrifugada, el sobrenadante recuperado, tratado con 150 μL de NaBH4 (20 mg/mL en NH4OH 1N) y posteriormente fue llevada a cabo la acetilación con 200 μL de anhídrido acético y 20 μL de 1-metilimidazol como catalizador; 2 mL de agua y 3 mL de cloroformo fueron agregados al material derivatizado y la fase clorofórmica fue recuperada y evaporada, así los acetatos de alditol fueron resuspendidos en acetona para su inyección en un cromatógrafo de gases Varian CP-3800 con detector FID (250°C), con columna capilar DB-23 de 30 m x 0.25 mm (210°C) y helio como gas acarreador a flujo constante de 3 mL/min. La integración de áreas fue hecho con el software MS Workstation versión 6.5 (SP1) (Varian Inc.), y los cálculos fueron realizados a partir de curvas estándares de ramnosa, fucosa, arabinosa, xilosa, manosa, galactosa y glucosa.

Celulosa

El pellet resultante del análisis de azúcares neutros se hidrolizó durante 5 h con H2SO4 concentrado y el contenido de azúcares totales se determinó por el método de antrona propuesto por Yemm y Willis (8); 100 μL del extracto se tomaron, adicionándoles 400 µL de agua destilada y 1000 μL de antrona al 0.2% en H2SO4 concentrado, se calentó en baño húmedo a 80°C por 10 min, posteriormente se enfrió en hielo y finalmente se tomó la lectura de las muestras a 620 nm en un espec- trofotómetro Cary 60 UV-Vis (Agilent Technologies). La determinación del contenido de celulosa se basó en una curva de calibración con glucosa y los resultados se expresaron en porcentaje.

Extracción de fenólicos libres y ligados

La extracción de fenólicos libres y ligados fue realizada de acuerdo al método de Urías-Orona et al. (9) con modificaciones. En la extracción de fenólicos libres se tomaron 100 mg de cascarilla de garbanzo y fueron suspendidos en 5 mL de metanol al 80%, enseguida la muestra fue tratada con flujo de argón durante 30 s y agitada a 200 rpm por 2 h. La muestra fue centrifugada a 4650 g, el sobrenadante fue recuperado y almacenado a -20°C hasta su análisis para fenólicos y capacidad antioxidante. En la extracción de fenólicos ligados, el pellet recuperado de la obtención de fenólicos libres fue tratado con 5 mL de NaOH 2M, flujo de argón por 30 s y agitado a 200 rpm por 4 h. Enseguida, el pH fue ajustado a 2.5 con HCl concentrado y centrifugado a 4650 g. El sobrenadante fue recuperado y se agregaron 5 mL de acetato de etilo en dos ocasiones. Los extractos de acetato de etilo fueron combinados y evaporados a 40°C con flujo de argón y almacenados a -20 °C. Al momento del análisis el extracto fue resuspendido en 3 mL de metanol al 80%.

Compuestos fenólicos y capacidad antioxidante Los ensayos de compuestos fenólicos y capacidad antioxidante fueron realizados de acuerdo a López Contreras et al. (10). La determinación del contenido de fenoles totales (FN) fue llevada a cabo utilizando el reactivo Folin-Ciocalteu, usando ácido clorogénico como estándar (0 a 200 mg/L) y el resultado fue expresado como miligramos equivalentes de ácido clorogénico por gramo de muestra (mgEAC/g). El contenido de flavonoides totales (FL) fue determinado con base al ensayo del cloruro de aluminio utilizando catequina como estándar (0 a 200 mg/L), y el resultado fue expresado como miligramos equivalentes de catequina por gramo de muestra (mgECat/g). El contenido de taninos condensados (TC) fue determinado con base en la prueba vainillina-HCl utilizando catequina como estándar (0 a 200 mg/L) y el resultado fue expresado como miligramos equivalentes de catequina por gramo de muestra (mgECat/g). La capacidad antioxidante fue evaluada con base en la reducción de absorbancia de los radicales 2,2-Difenyl-1-picrylhydrazilo (DPPH) y ácido 2,2-azino-bis(3-etilbenzotiazolin)-6-sulfónico (ABTS), utilizando Trolox como estándar (0 a 800 μmol/g) y expresados como micromoles equivalentes de Trolox por gramo de muestra (μmolET/g).

Análisis de datos

Los datos fueron expresados como media ± desviación estándar (yi = µ ± εi,n=4), obtenidos de los resultados de la estadística descriptiva para cada variable

evaluada; el software Minitab14.0 (Minitab, 2004) fue usado para estas determinaciones.

RESULTADOS

Análisis proximal

El contenido de humedad, cenizas, proteínas, grasa, carbohidratos, minerales y azúcares neutros se muestra en la Tabla 1. Los carbohidratos representaron el mayor contenido en la cascarilla de garbanzo, seguidos por proteína, humedad, cenizas y grasas. El contenido de fibra dietaria total fue de 78.8% siendo el principal componente polisacáridos no celulósicos (54.4%) seguido por la celulosa (24.4%).

El contenido de minerales encontrado en el presente estudio mostró en mayor proporción fue Ca, seguido por K y Mg (Tabla 2) con niveles de 9316, 7699 y 2799 ppm, respectivamente, mientras que Fe y Zn minerales esenciales en la nutrición humana con se encontraron en concentraciones de 83 y 29 ppm, respectivamente.

La Tabla 2 muestra la composición de azúcares neutros en la cascarilla de garbanzo, siendo los mayoritarios arabinosa (26.83%), galactosa (25.48%) y glucosa

(20.38%), seguidos por ramnosa (10.56%), xilosa (9.25%) y manosa (6.85%), mientras que el azúcar de menor concentración fue fucosa (0.64%).

Compuestos fenólicos y capacidad antioxidante

En la Tabla 3, se observa el contenido de compuestos fenólicos de la cascarilla de garbanzo. En fenoles totales las fracción libre presentó 1.50 mgEAC/g, mientras que el contenido de la fracción ligada fue de 0.11 mgEAC/g. En flavonoides totales el contenido de la fracción ligada y libre fue con 0.94 y 0.42 mgECat/g, respectivamente. En el contenido de taninos condensados la fracción libre y ligada arrojaron valores de 7.38 y 5.90 mgEAC/g, por lo que predomina la presencia de este grupo fenólico en la cascarilla de garbanzo. En cuanto a la capacidad antioxidante, la cascarilla de garbanzo presentó niveles de 2.81 y 2.35 μmolET/g en la fracción libre y ligada, respectivamente en el método DPPH, mientras que por el método ABTS la capacidad antioxidante fue mayor, observando que la fracción libre fue mayor a la ligada con 12.97 y 6.52 µmolET/g, respectivamente.

TABLA 1. Composición química de cascarilla de garbanzo (g/100g).

TABLA 2. Composición de azúcares neutros y minerales de cascarilla de garbanzo.

TABLA 3. Contenido total de compuestos fenólicos y capacidad antioxidante de cascarilla de garbanzo (Fracción Libre + Fracción Ligada).

DISCUSIÓN

Bose y Shams-Ud-Din (11) reportaron para cascarilla de garbanzo Bengal gram un contenido de 5.25 de proteína, 4.79 grasa y 4.79 ceniza (g/100g), donde la ceniza mostró una diferencia de 3.49 g con respecto a la obtenida en este estudio. La fibra dietaria total es uno de los componentes más importantes en las legumino- sas y se clasifica en fracciones soluble e insoluble, incluyendo la primera gomas, mucilagos, pectinas y algunas hemicelulosas, mientras que la segunda se compone de celulosa, lignina, y el resto de las hemicelulosas son parte de la fracción insoluble. Khan et al. (12) reportaron contenidos de 22% de fibra dietaria total, 6.5% de celulosa y 2.7% de pectina para grano de garbanzo sin cascarilla, observándose una gran diferencia con el presente estudio, ya que la cascarilla del grano se constituye principalmente de estos componentes. Bose y Shams-Ud-Din (11) utilizaron cascarilla de garbanzo a diferentes concentraciones en la formulación de galletas tipo cracker biscuits y observaron un incremento del 2.58% en el contenido de fibra cruda. Los carbohidratos son una fuente nutritiva importante y son clasificados en monosacáridos, oligosacáridos y polisacáridos; Wood y Grusak (13) reportaron un contenido de carbohidratos en grano entero de garbanzo tipo Desi de 51-65%, mientras que para el tipo Kabuli el 54-71%.

Las leguminosas son una fuente importante de minerales indispensables para el organismo humano, dentro de los principales en la nutrición humana están el Ca, Fe y Zn. Sandberg (14) evaluó el contenido de minerales en grano entero de garbanzo y reportó valores de 69, 35, 1240, y 1550 ppm para Fe, Zn, Ca y Mg, respectivamente, siendo los niveles de Fe y Zn cercanos a lo encontrado en el presente estudio, sin embargo sus niveles de Ca y Zn son inferiores a nuestros resultados. La biodisponibilidad de minerales en leguminosas está relacionado con el contenido de ácido fítico ya que este tiene un efecto negativo en su absorción. En este sentido, Wang et al. (15) reportó para garbanzo tipo Kabuli un contenido de 9.6 g/kg de ácido fítico el cual fue menor al compararlo con seis variedades de frijol con 12.2 g/kg en promedio, lo que sugiere que el garbanzo tiene mayor biodisponibilidad de minerales que el frijol, siendo este último la leguminosa la de mayor consumo en México.

Así mismo, en las leguminosas están presentes azúcares digeribles e indigeribles; en el grano entero de garbanzo han sido reportados azúcares libres (mono- sacáridos) como glucosa y galactosa en niveles de 700 y 50 mg/100g, respectivamente (16). En la determinación de los monosacáridos cuantificados para la cascarilla de garbanzo, arabinosa y galactosa se encuentran como componentes mayoritarios, lo que indica la presencia de arabino galactanos y ramnogalacturonanos los cuales son componentes de las pectinas (17).

Los compuestos fenólicos ligados se encuentran interaccionando con las hemicelulosas presentes en la fibra dietaria mediante un enlace tipo éster, lo cual explica su mayor contenido en las fracciones ligadas sometidas a condiciones de alcalinidad durante su extracción, ya que bajo estas condiciones se lleva a cabo la ruptura de este enlace (18). Segev et al. (19) reportaron en cascarilla de garbanzo tipo Kabuli un con- tenido de fenoles totales entre 0.2-1.1 mgECat/g, mientras que Kanatt et al. (3) reportaron en cascarilla de garbanzo Bengal gram, fenoles y flavonoides totales un contenido de 70 y 10 mgECat/g respetivamente; la diferencia observada con estos autores se debe al método de extracción empleado, así como a las características propias del grano, principalmente el color de la cascarilla. Diversos estudios han empleado diferentes técnicas como el descascarillado del grano, germinado, remojo y molienda con la finalidad de disminuir el tiempo de cocción, mejorar el sabor, la biodisponibilidad de minerales, proteínas y otros nutrientes, sin embargo cabe resaltar que esta acción afecta considerablemente la pérdida de los compuestos fenólicos presentes en este material vegetal (20). Los taninos son un grupo de polifenoles solubles en agua, forman complejos con polisacáridos y proteínas. Éstos se clasifican en taninos hidrolizables y taninos condesados (21). Han y Baik (22) reportaron para el grano de garbanzo una actividad antioxidante por ABTS en la fracción libre y ligada de 1.5 y 0.5 μmolET/g, respectivamente, los cuales están por debajo a lo obtenido en este estudio, con una diferencia del 11.47 y 6.02 mmolET/g. Ziu-Ul-Haq et al. (23) reportaron para garbanzo tipo Desi un contenido de fenoles totales, flavonoides totales y taninos condensados de 0.92-1.12, 0.79-0.99 y 0.58-0.69 mg/g, respectivamente, que fueron más bajos a lo reportado en este estudio, aunque la actividad antioxidante por DPPH y ABTS reportada por estos autores fue de 1.05-1.24 y 37.24-45.32 mmolTE/g, donde este último fue mayor a los obtenidos en este estudio.

CONCLUSIONES

La cascarilla de garbanzo tiene contenido de proteína considerable, un alto contenido de fibra dietaria total, además presenta contenidos elevados contenidos de Ca, K y Mg, así como de los azúcares arabinosa, galactosa, glucosa. Finalmente, también presenta contenidos elevados de compuestos fenólicos y altos niveles de capacidad antioxidante. Por estas características, la cascarilla de garbanzo puede considerarse con un buen valor nutritivo y funcional apto para mejorar la salud de los consumidores. También es posible considerar la cascarilla del garbanzo como una alternativa para potencializar la funcionalidad de otros alimentos.

AGRADECIMIENTOS

Al Programa de Apoyo a la Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (PAICYT) 2015 de la Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León por el financiamiento otorgado. A Rosabel Vélez de la Rocha y Werner Rubio Carrasco, por la asistencia técnica brindada.

REFERENCIAS

1. De Almeida Costa GE, Da Silva Queiroz Monici K, Pissini Machado Reis SM, Costa de Oliveira A. Chemical composition, dietary fiber and resistant starch contents of raw and cooked pea, common bean, chick pea and lentil legumes. Food Chem. 2006; 94 (3), 327-330.

[ Links ]2. Campos-Vega R, Loarca Piña G, Oomah BD. Minor components of pulses and their potential impact on human health. Food Res Int. 2010; 43 (2), 461-482.

[ Links ]3. Kanatt SR, Arjun K, Sharma A. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of legume hulls. Food Res Int. 2011; 44 (10), 3182-3187.

[ Links ]

4. Tharanathan RN, Mahadevamma S. Grain legumes a boon to human nutrition. Trends Food Sci Tech. 2003; 14 (12), 507-518.

Links ] font-family: "Arial",sans-serif; color: navy;" lang="EN-US"> 5. Scalbert A, Manach C, Morand C, Rémésy C, Jiménez L. Dietary polyphenols and the prevention of diseases. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2005; 45 (4), 287-306.

[ Links ]6. Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, Rémésy C, Jiménez L. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004; 79 (5), 727-747.

[ Links ]

7. Official Methods of Analysis of Association of Official Analytical Chemist International (AOAC). 1998; 16th Edition, 4th Revision. AOAC International Maryland, USA.

[ Links ]

8. Yemm EW, Willis AJ. The estimation of carbohydrates in plants extracts by anthrone. Biochem J. 1954; 57 (3), 508-514.

[ Links ]

9. Urias-Orona V, Heredia JB, Muy Rangel D, Niño Medina G. Acidos fenólicos con actividad antioxidante en salvado de maíz y salvado de trigo. Ecosistemas y Recursos Agropecuarios. 2016; 3 (7), 43-50.

[ Links ]

10. López-Contreras JJ, Zavala García F, Urias Orona V, Martínez ávila GCG, Rojas R, Niño-Medina G. Chromatic, phenolic and antioxidant properties of Sorghum bicolor genotypes. Not Bot Horti Agrobo. 2015; 43 (2), 366-370. [ Links ]

11. Bose D, Shams-Ud-Din M. The effect of chickpea (Cicer arietinum) husk on the properties of cracker biscuits. J Bangladesh Agril Univ. 2010; 8 (1), 147-152.

[ Links ]

12. Khan AR, Alam S, Ali S, Bibi S, Khalil IA. Dietary fiber profile of food legumes. Sarhad J Agric. 2007; 23 (3), 763-766.

[ Links ]13. Wood JA, Grusak MA. Nutritional value of chickpea. In: Chickpea breeding and management. [Yadav SS, Redden R, Chen W, Sharma B editors]. Wallingford, UK: CABI International. 2007; 101-142.

[ Links ]

14. Sandberg AS. Bioavailability of minerals in legumes. Brit J Nutr. 2002; 88 (S3), S281-S285.

[ Links ]15. Wang N, Hatcher DW, Tyler RT, Toews R, Gawalko EJ. Effect of cooking on the composition of beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and chickpeas (Cicer arietinum L.). Food Res Int. 2010; 43 (2), 589-594.

[ Links ]

16. Sánchez-Mata MC, Peñuela-Teruel MJ., Cámara Hurtado M., Díez Marqués C, Torija Isasa ME. Determination of Mono, and oligosaccharides in legumes by high performance liquid chromatography using an amino-bonded silica column. J Agric Food Chem. 1998; 46 (9), 3648-3652.

[ Links ]17. Willats WGT, Knox JP, Mikkelsen JD. Pectin: new insights into an old polymer are starting to gel. Trends Food Sci Tech. 2006; 17 (3), 97-104. [ Links ]

18. Kroon PA, Faulds CB, Ryden P, Robertson JA, Williamson G. Release of covalently bound ferulic acid from fiber in the human colon. J Agric Food Chem. 1997; 45 (3), 661-667. [ Links ]

19. Segev A, Badani H, Kapulnik Y, Shomer I, Oren-Shamir M, Galili S. Determination of polyphenols, flavonoids, and antioxidant capacity in colored chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). J Food Sci. 2010; 75 (2), S115-S119.

[ Links ]

20. Oghbaei M, Prakash J. Effect of primary processing of cereals and legumes on its nutritional quality: a comprehensive review. Cogent Food & Agriculture. 2016; 2 (1), 1-14.

[ Links ]

21. Han X, Shen T, Lou H. Dietary polyphenols and their biological significance. Int J Mol Sci. 2007; 8 (9), 950-988.

[ Links ]

22. Han H, Baik BK. Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of lentils (Lens culinaris), chickpeas (Cicer arietinum L.), peas (Pisum sativum L.) and soybeans (Glycine max), and their quantitative changes during processing. Int J Food Sci Tech. 2008; 43 (11), 1971-1978. [ Links ]

23. Zia-Ul-Haq M, Iqbal S, Ahmad S, Bhanger MI, Wicz kowski W, Amarowicz R. Antioxidant potential of Desi chickpea varieties commonly consumed in Pakistan. J Food Lipids. 2008; 15 (3), 326-342. [ Links ]

Samuel Durán Agüero, Gustavo Cediel Giraldo, Jerusa Brignardello Guerra

Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud. Universidad San Sebastián. Chile. Colegio de Nutricionistas Universitarios de Chile.

SUMMARY. Objective: To establish the relationship between sleep duration, nutritional status and caffeinated beverage consumption patterns in school-age Chilean children. Method: The study was conducted in 805 school age children, between 6 and 10 years old from 6 neighbor hoods in Santiago, Chile. Parents completed a questionnaire, which assessed sleep duration, physical activity and food intake. Anthropometric measurements were completed for children. Results: 52.6% of school age children were obese and 46.4% slept the recommended amount (≥10 hours). Normal weight subjects slept significantly more hours than obese participants, 9.8 ± 0.9 vs. 9.6 ± 0.9, respectively. Sleep duration during the week was inversely associated to obesity (OR: 3.5, 95% CI 1.3-9.2). Children drank the following beverages at night: caffeinated soft drinks (52.2 %), coffee and/or tea (32.6%) and 21.2 % both soft drinks and coffee tea caffeine beverages Conclusion: Over half of this sample of school-age Chilean children slept less than the recommended (≥10 hours) amount, with obese participants sleeping less than normal weight subjects. The intake of caffeine products in particular, caffeinated soft drinks, was higher during the night in both groups.

Key words: Sleep, obesity, nutritional status, caffeine.

RESUMEN. Relación entre el estado nutricional y la cantidad de sueño en escolares chilenos. Objetivo: establecer la relación entre cantidad de sueño, estado nutricional y consumo de cafeína en escolares Métodos: El estudio fue realizado en 805 escolares, entre 6 a 10 años de 6 comunas de Santiago de Chile. Los padres completaron las encuestas de sueño, actividad física y consumo de alimentos. A los escolares se les realizó una evaluación antropométrica. Resultados: El 56,2% de los escolares era obeso, el 46,4% dormía menos de lo recomendado (≥10 horas). La cantidad de sueño fue significativamente mayor en los escolares normal peso que en los obesos 9,8 ± 0,9 vs 9,6 ± 0,9, respectivamente. La cantidad de sueño durante la semana fue inversamente asociada a obesidad (OR: 3,5; 95% CI 1,3-9,2). Los escolares bebían en la noche antes de dormir: bebidas carbonadatas con cafeína (52,2%), café y/o té (32,6%) y un 21,2% ambos tipos de bebidas. Conclusión: Más de la mitad de esta muestra de niños en edad escolar, dormia menos de la cantidad recomendada (≥ 10 horas), los escolares obesos dormían menos de sujetos de peso normal. Además se observa una ingesta en la noche de bebidas carbonatadas con cafeína elevada en ambos grupos.

Palabras clave: Sueño, obesidad, estado nutricional, cafeina.

Recibido: 10-09-2016 Aceptado: 21-11-2016.

INTRODUCTION

Childhood obesity is considered a worldwide health problem (1). It increases the risk of the other diseases such as diabetes, dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension and has cardiovascular consequences in adulthood (2). In the last 2 decades, Chile has undergone an epide- miological transition, where pediatric under-nutrition was replaced by overweight and obesity (3). The main strategy for the prevention and treatment against this epidemic has been a healthy diet and physical activity (4). Results of interventions, however, have not been completely effective or positive (1,4,5). Interventions that address other risks factors are needed to reduce obesity and improve intervention results. Some studies have shown an association between reduced sleep du- ration and childhood overweight, especially in young children (6-8).

Sleep behavior, a healthy diet and physical activity have an important role in the physiological processes of growth, development and health (9). Short sleep du- ration is related to changes in levels of leptin, ghrelin and cortisol, in addition to glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity (10). Additional studies have confirmed also that slept deprivation has an impact on increased hunger sensation and daytime appetite (11,12).Thus, short sleep duration is related to the risk of obesity (7). Encouraging adequate sleep as part of an intervention may be novel, effective and complementary to encouraging healthy eating habits and physical activity for the prevention and treatment of obesity (13). In recent years, an increasing number of population studies on the association between sleep and obesity among children have become available. However, similar information is not available for a pediatric large Chilean population or studies that evaluate the association bet- ween caffeine beverages and the sleep duration. Therefore, the aim of this study was to establish the relationship between sleep duration, nutritional status and caffeinated beverage consumption patterns in school-age Chilean children.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population: Twelve primary schools with similar socio- economic characteristics from Santiago, Concepción and Valparaíso, Chile. Participated in the study between August 2014 and October 2015. The sample size was calculated based on a previous study (6) and was powered to detect a difference in sleep du- ration between normal and obese participants of 0.5 hour with a standard error of α=0.05 and 0.9 power.

Inclusion criteria included being between 6 and 10 years old; enrolled in the test school the day of the evaluation, and not being currently treated for sleep disturbance or depression. A total of 887 school-age children between 6 and 10 years old were approached to participate in the study and 805 completed the questionnaires (90.7%). All parents or caregivers provided signed informed consent and children provided informed assent before participation. The institutional re- view board at the Universidad San Sebastián, Chile approved this study.

Anthropometric Measurements: Trained personal measured body weight and heigh. Weight was measured without shoes or belts in light clothing, and recor- ded to the nearest 0.1 kg with a digital scale (Seca 813 digital electronic floor scale). Height was measured with a stadiometer to the nearest 1 mm without shoes. WC was measured standing with a non-elastic tape, which was applied horizontally midway between the lowest rib margin and the iliac crest. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). The used BMI reference was the National Center for Health Statistics/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 Growth Charts (14), which has been endorsed by the Chilean Ministry of Health for its use. Children were classified as obese if their BMI was >95th percentile, non-obese if the BMI was >10th <85th percentile and overweight if the BMI was ≥85 th ≤ 95 th but this group was not considered in our study.

Sleep Duration: Parents were asked to complete the 22-item Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire (PSQ) about their children. The PSQ provides high validity and sensitivity greater than 0.8.

Eating and Physical Activity Habits: Parents were asked about the contents of the last meal of the day, specifically caffeine intake. They were also asked to report the daily physical activity habits of their children. Adequate sleep duration was definedas sleep ≥10 hours per night (8).

Statistics: Data was entered using Excel. Normality of continuous variables was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk goodness of fit test. For normally distributed variables we used the Student t-test and the Mann Whitney U test was used for non normally distributed variables. Logistic regression was used to test the relationship between sleep duration, caffeine intake, physical activity and the dependent variable nutritional status. The α was set as <0.05 for statistical significance. We analyzed data using SPSS version 19.0, Chicago, IL.

RESULTS

We studied 805 school-age children of which 57% were boys; 47.4% were normal weight (n=382) and 52.6% were obese (n=423). Table 1 shows differences in weight, height and BMI by nutritional status. Forty six percent of students slept the recommended amount per night (≥10 hours). On weekdays normal weight children slept significantly more than obese students: 9.8 ± 0.9 hours vs 9.6 ± 0.9. Differences did not persist for the weekend. Normal weight girls sleep more hours on weekdays and on weekends (p<0.05). This differs from boys who only had significant differences for the weekend (p<0.05). We found no sex differences in sleep duration during the week and on the weekend.

Comparing sleep duration on weekdays by nutritional status and age among girls (Figure 1) we found that as age increased, sleep duration decreased. Six and 7- year old girls sleep significantly more compared to 10 year old girls. Normal weight girls ages 8 and 9 slept significantly more than obese girls of the same ages. We saw similar trends at other ages, but these did not reach statistical significance. We found no differences in sleep duration on the weekend.

FIGURE 1. Comparison of weekday sleep duration by age and nutritional status: males only.

FIGURE 2. Comparison of weekday sleep duration by age and nutritional status: females only.

TABLE 2. Association between nutritional status.

Figure 2 shows that for boys bet- ween 6 and 10 years, as age increases, sleep duration decreases (p<0.05). These differences were not observed for the weekend. We found no differences between normal weight and obese boys of the same age with respect to sleep duration.

Table 2 shows that sleeping <10.5 hours per night on a weekday was associated with greater odds of obesity (OR: 3.5, 95%CI 1.3-9.2). We found no other significant associations with obesity risk: sleep duration <10 or 11 hours, consumption of caffeine before bed, exercise and others (all p>0.05).

According to parent report, 32.6% of children drank coffee and tea after 8PM, 52.2% drank soft drinks and 21.2% regularly drink coffee, tea or soft drinks before bed. With respect to physical activity, only 20.4% of students reach the recommended amounts of ≥ 3 times per week for ≥ 30 minutes, with no significant differences by nutritional status. Two percent reported never exercising.

DISCUSSION

Among other behavioral changes in industrialized countries, a decrease in total sleep duration has been noted (13). Adolescents all over the world use computers and watch television for prolonged periods, postponing sleep onset and thus decreasing total sleep duration16. In the current study we observed that obese students slept significantly less during the week than normal weight participants, but no differences were found on the weekend. Both groups responded to the sleep restriction during the week by compensating on the weekend. Observational studies conducted among children have shown sleep duration is negatively associated with BMI and obesity risk (6,8). Chen (5) ob- served that children who slept <10 hours had a 58% higher risk of overweight or obesity (combined OR=1.58; 95% CI 1.26-1.98). For every additional hour of sleep, the risk of overweight/obesity was reduced by 9% (OR=0.91; 95% CI 0.84-1). This result is similar to that in our study in which sleeping <10.5 hours during the week was associated with obesity (OR: 3.5, 95% CI 1.3-9.2). In a study conducted among Chinese adolescents, researchers showed that short sleep duration was significantly associated with greater adiposity and less lean mass in females (15). Another study demonstrated that sleeping more in the school- age period is a protective factor for obesity (OR=0.2, 95% CI 0.08-0.85) (9). The association between sleep duration and obesity and sex differences is supported by several studies (13), however we did not find these differences in our analysis. One possible explanation could be that girls are less affected by sleep duration than boys. From an evolutionary perspective, boys may be more vulnerable to environmental stress in child hood, compared to girls (16).

A national survey conducted in the U.S. (2005) showed that 45% of adolescents sleep less than the recommended amount (8 hours or more per night) and 31% are on the border. We found similar values in our study (46%). In our sample of school-age children, we also found that as age increased, sleep duration decreased. Our findings are in line with those of a representative sample of U.S. adolescents conducted by the National Sleep Foundation in 2006 that found that sleep duration was primarily decreased because subjects were going to bed later (17).

A recent study has reported a positive association between physical activity and increased sleep duration in children (18). However we did not find any association between physical activity and sleep duration, albeit the higher sedentary behavior in our sample (79.6%) compared to other studies conducted in school-age children (11,19).

Caffeinated and soft drinks were consumed regularly in both groups before bed, but is not possible to determine is this consumption has a possible disruptive role in sleep duration in obese children.

Strengths of this study include having a representative sample of public school children in Santiago and highly trained personnel carry out the anthropometric measurements. Several limitations must also be mentioned. Our study is cross sectional, thus causality cannot be determined. We used self reported measures to determine sleep duration, physical activity, and eating habits. This methodology may have introduced some bias. A final limitation is that screen time (television and/or computer) was not assessed. We consider this narrow age because Tanner staging assessment was not allowed to assess by school rules, hence a puberty assessment in this group could not be done. This is a limitation of our study.

CONCLUSION

Our results show that short sleep duration during the week (<10.5 hours) is associated with obesity in 6 to 10 year old school children and that obese children sleep less during the week compared to their nor- mal weight peers. Further research is needed to understand the impact of lack of sleep on children obesity, but also public health obesity interventions should include messages associated with adequate sleep duration in children.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For their time and helpful suggestions, we thank all of the teachers that collaborated on this project.

REFERENCES

1.Sharma M. International school-based interventions for preventing obesity in children. Obes Rev 2007; 8: 155– 67.

2.Herouvi D, Karanasios E, Karayianni C, Karavanaki K. Cardiovascular disease in childhood: the role of obesity. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172(6):721-32.

3.Atalah E, Amigo H, Bustos P. Does Chile's nutritional situation constitute a double burden?. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(6):1623S-7S.

[ Links ]

4.Flodmark CF, Marcus C, Britton M. Interventions to prevent obesity in children and adolescents: a systematic literature review. Int J Obes 2006; 30: 579-89.

[ Links ]

5.van Sluijs EM, McMinn AM, Griffin SJ. Effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity in children and adolescents: systematic review of controlled trials. BMJ 2007; 335(7622):703. [ Links ]

6.Durán Agüero S, Haro Rivera P. Association between the amount of sleep and obesity in Chilean school children. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2016;114(2):114-119. [ Links ]

7.Cespedes EM, Hu FB, Redline S, Rosner B, Gillman MW, Rifas Shiman SL, et al. Chronic insufficient sleep and diet quality: Contributors to childhood obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(1):184-90. [ Links ]

8.Chen X, Beydoun MA, Wang Y. Is sleep duration associated with childhood obesity? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity 2008; 16(2): 265–74.

9.Zaqout M, Vyncke K, Moreno LA, De Miguel-Etayo P, Lauria F, Molnar D, et al. Determinant factors of physical fitness in European children. Int J Public Health. 2016. [Epub ahead of print] [ Links ]

10.Buxton OM, Cain SW, O'Connor SP, Porter JH, Duffy JF, Wang W, et al. Adverse metabolic consequences in humans of prolonged sleep restriction combined with circadian disruption. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4(129):129ra43.

[ Links ]

11.Spiegel K, Tasali E, Leproult R, Scherberg N, Van Cauter E. Twenty-four-hour profiles of acylated and total ghrelin: relationship with glucose levels and impact of time of day and sleep. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96(2):486-93. [ Links ]

12.Spiegel K, Tasali E, Penev P, Van Cauter E. Brief communication: Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141(11):846-50.

13. [ Links ]Magee CA, Iverson DC, Huang XF, Caputi P. A link between chronic sleep restriction and obesity: methodological considerations. Public Health 2008; 122:1373–81.

14.National Center for Health Statistics/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2000). 2000 CDC growth charts: United States. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/.

[ Links ]

15.Yu Y, Lu BS, Wang B, Wang H, Yang J, Li Z, et al. Short sleep duration and adiposity in Chinese adolescents. Sleep 2007; 30(12):1688-97.

[ Links ]

16.Morselli LL, Guyon A, Spiegel K.. Sleep and metabolic function. P flugers Arch. 2012;463(1):139-60. [ Links ]

17.National Sleep Foundation. Sleep in America Poll. Available at: http://www.sleepfoundation.org/sites/default/files/2006_summary_of_findings.pdf.

18. [ Links ]Khan MK, Chu YL1, Kirk SF, Veugelers PJ. Are sleep duration and sleep quality associated with diet quality, physical activity, and body weight status? A population-based study of Canadian children. Can J Public Health. 2015;106(5):e277-82.

[ Links ]

19.Villagrán Pérez S, Rodríguez-Martín A, Novalbos Ruiz JP, Martínez Nieto JM, Lechuga Campoy JL. Hábitos y estilos de vida modificables en niños con sobrepeso y obesidad. Nutr. Hosp 2010;25(5): 823-31. [ Links ]

UNA TRAYECTORIA DE LUZ

En Junio de 1950 el Instituto Nacional de Nutrición, INN, de Venezuela, publica por primera vez el Volumen 1, Número 1 de Archivos Venezolanos de Nutrición, AVN, (...) una publicación científica dedicada exclusivamente a la Nutrición.

En los siguientes 15 años AVN publica sin interrupción 29 Números distribuidos en 16 Volúmenes. Durante la celebración de la Tercera Conferencia sobre los Problemas de Nutrición en la América Latina, en 1953, se consideró extraoficialmente la creación de una revista latinoamericana de nutrición.

Dos años mas tarde en 1955, apareció en AVN un Editorial que bajo el título Hacia una Revista Latinoamericana de Nutrición , dejaba vislumbrar el inicio de esta realidad. En Noviembre de 1964 se celebra en Caracas las Primeras Jornadas Venezolanas de Nutrición y allí se plantea la necesidad de la creación de una revista latinoamericana con el fin de centralizar en ella los numerosos trabajos que se elaboran en el hemisferio, ya que la mayoría de ellos se encuentran dispersos en publicaciones de difícil acceso. En consonancia con este criterio, durante el Congreso de Nutrición del Hemisferio Occidental celebrado en Noviembre de 1965 en Chicago, Illinois, se funda la Sociedad Latinoamericana de Nutrición, SLAN, y uno de sus principales objetivos es la publicación de una revista que recoja las investigaciones que sobre nutrición se llevan a cabo en Latinoamérica.

En un hermoso gesto, el Gobierno de Venezuela, en comunicación firmada por el Dr. Miguel Octavio Russa, Director Ejecutivo del Instituto Nacional de Nutrición dirigida al Dr. Conrado F. Asenjo, Presidente de la recién creada SLAN, cede la revista Archivos Venezolanos de Nutrición para que esta sea transformada en el órgano oficial divulgativo de la Sociedad bajo el nombre de Archivos Latinoamericanos de Nutrición, ALAN. Cito textualmente parte de la comunicación del Dr. Russa: La única condición para este traspaso será la de que se mencione en el rótulo externo de la nueva publicación el hecho de que fue creada originalmente como Archivos Venezolanos de Nutrición. Bajo este claro lineamiento, AVN, venezolana publicación, amplía su cobertura para ingresar en el ámbito latinoamericano.

El Volumen 15, Número 2 de 1965 es el último Archivos Venezolanos de Nutrición. A continuación la Sociedad Latinoamericana de Nutrición inicia en Caracas la publicación de Archivos Latinoamericanos de Nutrición bajo la responsabilidad editorial del Dr. Werner Jaffé, con el Volumen 16, Número 1, Septiembre 1966, de portada azul marino a 1/12 y en su centro la frase requerida por el INN. Durante los próximos 11 años, ALAN es publicado en Caracas y en 1978 la edición del Volumen 78 es trasladada al INCAP en Guatemala hasta el Volumen 41, 1991, período en el cual el Dr. Ricardo Bressani desempeña el cargo de Editor General. La revista regresa a Caracas para continuar su publicación con el Volumen 42, Marzo 1992, con estreno de nueva portada a 1/8, fondo blanco, con letras azules y espigas de trigo doradas. Entre 1992 y 2016, ALAN ha publicado ininterrumpidamente 24 Volúmenes con un total de 96 Números y 14 Suplementos.

En 1994 ALAN recibe el Premio Anual Tulio Arends otorgado por el CONICIT, (actualmente FONACIT) Venezuela, a la mejor revista científica y tecnológica nacional y en 1995 la Mención Honorífica al mismo Premio. En Febrero 2007 el FONACIT, en una Evaluación de Mérito de 74 revistas científicas y tecnológicas venezolanas, otorga a ALAN el cuarto lugar quedando ubicado en la segunda posición dentro del área de Biomedicina.

En la Evaluación Integral de 2010, ALAN obtiene una calificación de 80 puntos, para quedar en el quinto lugar sobre un total de 22 revistas. Desde 2016 ALAN es indexado en la Base de Datos MEDES, por gentil invitación de Iniciativa MEDES-MEDicina en Español, en nombre de la Fundación Lilly. Este merecido homenaje al prestigio de ALAN pone a disposición de los profesionales sanita rios de habla hispana, una herramienta de consulta bibliográfica cuyas características mas apreciadas son la calidad y la actualización continua, así como la evaluación rigurosa de sus contenidos. En Septiembre de 1968 se realiza en Caracas el primer Congreso de la SLAN y el Editorial del Volumen 19 de ALAN recoge un emotivo discurso del Dr. José Eduardo Dutra de Oliveira, su Presidente, bajo el título de Saudacaos aos participantes do 1 Congresso da SLAN y el Volumen 20, Marzo 1970, incluye el Suplemento donde se da a conocer el informe de los Grupos Asesores sobre los temas discutidos en el Congreso. La presencia de Archivos Latinoamericanos de Nutrición como órgano divulgativo oficial de la SLAN, ha sido relevante en estos eventos científicos. A continuación un listado de los 17 Congresos de la SLAN realizados, quien lo presidió, ciudad, país y fecha. El Congreso XVIII está fijado para 2018 en México.

Congreso I . José E. Dutra de Oliveira. Caracas, Venezuela. Septiembre 1968

Congreso II . Fernando Monckeberg B. Viña del Mar, Chile. Diciembre 1970

Congreso III . Antonio Bacigalupo. Guatemala, Guatemala. Septiembre 1972

Congreso IV . Werner Jaffé. Caracas, Venezuela. Noviembre 1976

Congreso V . Hector Bourges. Puebla, México. Agosto 1980

Congreso VI . Juan Claudio Sanahuja. Buenos Aires, Argentina. Agosto 1982

Congreso VII . Alfredo Lam Sanchez. Brasilia, Brasil. Noviembre 1984

Congreso VIII . Sergio Valiente. Viña del Mar, Chile. Noviembre 1988

Congreso IX . Jaime Ariza Macía. San Juan, Puerto Rico. Septiembre 1991

Congreso X . Eleazar Lara Pantin. Caracas, Venezuela. Noviembre 1994

Congreso XI . Hernán Delgado. Guatemala, Guatemala. Noviembre 1997

Congreso XII . Alejandro O Donnell. Buenos Aires, Argentina. Noviembre 2000

Congreso XIII . Adolfo Chávez V. Acapulco, México. Noviembre 2003

Congreso XIV . Helio Vannuchi. Florianópolis, Brasil. Noviembre 2006

Congreso XV . Eduardo Atalah Samur. Santiago, Chile. Noviembre 2009

Congreso XVI . Manuel Hernández Triana. La Habana, Cuba. Noviembre 2012

Congreso XVII . María N. García-Casal. Punta Cana, R. Dominicana. Noviembre 2015

Al presente la edición de ALAN está en Caracas y su recorrido ejemplar en el Hemisferio Americano. ...debemos tener muy presente que su éxito como revista científica de reconocida responsabilidad y prestigio dependerá exclusivamente de los artículos originales de alta calidad y valor que aparezcan en sus páginas. Este es el reto que nosotros, los miembros de la SLAN, tenemos que aceptar si pretendemos que, con el correr del tiempo, nuestra revista llegue a ser algún día una de primer orden en su género, que es precisamente lo que nos proponemos. Tomado del Editorial, Volumen 16, Septiembre 1966, de Conrado F. Asenjo. Primera Directiva de la SLAN.

José Félix Chávez Pérez

Editor General 1997 - 2017

^rND^1A01^nBetty^sMéndez-Pérez^rND^1A01^nJoana^sMartín-Rojo^rND^1A01^nMaura^sVásquez^rND^1A01^nGuillermo^sRamírez^rND^1A01^nCoromoto^sMacías-Tomei^rND^1A01^nMercedes^sLópez-Blanco^rND^1A01^nBetty^sMéndez-Pérez^rND^1A01^nJoana^sMartín-Rojo^rND^1A01^nMaura^sVásquez^rND^1A01^nGuillermo^sRamírez^rND^1A01^nCoromoto^sMacías-Tomei^rND^1A01^nMercedes^sLópez-Blanco^rND^1A01^nBetty^sMéndez-Pérez^rND^1A01^nJoana^sMartín-Rojo^rND^1A01^nMaura^sVásquez^rND^1A01^nGuillermo^sRamírez^rND^1A01^nCoromoto^sMacías-Tomei^rND^1A01^nMercedes^sLópez-BlancoConcordancia entre los indices de masa corporal nacional e internacional, como predictores de la composición corporal en adolescentes premenárquicas y menárquicas

Betty Méndez-Pérez, Joana Martín-Rojo, Maura Vásquez, Guillermo Ramírez, Coromoto Macías-Tomei, Mercedes López-Blanco

Universidad Central de Venezuela. Universidad Simón Bolívar. Fundación Bengoa para la Alimentación y Nutrición. Caracas Venezuela

RESUMEN

El uso de referencias nacionales e internacionales para diagnosticar el estado nutricional es una discusión de larga data, debido a las discrepancias en los resultados. En este trabajo se contrastó la capacidad del índice de masa corporal (IMC) para predecir composición corporal, diagnosticada por área grasa (AG) y/o área muscular (AM), utilizando la referencia nacional (ENCDH) vs la internacional (OMS, 2007). Este estudio comparativo fue aplicado sobre una subpoblación de la base de datos de la Unidad de Bioantropología, Actividad Física y Salud, de 364 adolescentes femeninas, escolarizadas, entre 10 y 15 años, de distintas regiones venezolanas. Se calculó el coeficiente Kappa ponderado para medir la concordancia del IMC por ambas referencias, se determinó la precisión del IMC en cada caso, utilizando medidas de sensibilidad y especificidad. Se estimaron razones de verosimilitud diagnóstica para comparar el desempeño de ambos clasificadores de composición corporal. El índice Kappa ponderado mostró mayor concordancia en AG (0,64) que en AM (0,51). La presencia de la menarquia incrementó las concordancias: AG (0,63) y AM (0,59) con respecto a las pre-menárquicas: AG (0,46) y AM (0,35). Las razones de verosimilitud diagnóstica positivas y negativas resultaron consistentemente mayores que la unidad, tanto para la predicción de AM como AG, siendo siempre superiores en ENCDH que en OMS. Estos hallazgos muestran que en adolescentes pre-menárquicas la referencia ENCDH es más indicativa para el déficit y el exceso en área muscular, que la OMS, mientras que esta última es más indicativa del exceso en área grasa en adolescentes pre-menárquicas.

Palabras clave: Menarquia, composición corporal, concordancias, razones de verosimilitud, referencia nacional e internacional, Venezuela.

SUMMARY.

Concordance between national and international bodymass index as a predictor of body composition in premenarcheal and menarcheal adolescents. Use of national and international references for the diagnosis of nutritional status is controversial. Concordance between national and international body mass index as predictors of body composition in 364 premenarcheal and menarcheal female adolescents (ages 10-15), classified according to occurrence of menarche, that were part of the database of the bioanthropology, physical activity and health unit, were evaluated. This study compares the capacity of body mass index (BMI) to predict body composition, diagnosed by upper arm fat area (UFA) and/ or upper arm muscle area (UMA), using national reference (ENCDH) vs International (WHO, 2007). The weighted Kappa coefficient was applied to evaluate the concordance between BMI by national and international references, as well as to assess the precision of BMI by means of sensibility and specificity. Additionally, diagnostic verisimilitude ratio was estimated to measure the efficiency of both references in the classification of body composition. The weighted Kappa showed greater concordance in UFA (0.64) versus UMA (0.51). The presence of menarche increased the concordances: UFA (0.63) and UMA (0.59) with respect to premenarcheal girls: UFA (0.46) and UMA (0.35). The positive and negative diagnostic likelihood ratios were consistently greater than one, for fat and muscle area, especially when using ENCDH reference. The findings suggest that prevalence of deficit or excess in UMA was more sensitive with the BMI_ENCDH than with the BMI_WHO, in premenarcheal girls. On the other hand, WHO was more sensitive to predict UFA excess in the same group.

Key words: Menarche, body composition, weighted Kappa coefficient, diagnostic likelihood ratios, international and national growth references, Venezuela.

Recibido: 29-07-2016

Aceptado: 24-11-2016INTRODUCCIÓN

La evaluación del estado nutricional y de la composición corporal, ésta última como elemento determinante del primero, es un objetivo prioritario en el campo de la epidemiología nutricional y la salud pública. Ambos indicadores son utilizados en la literatura especializada como una herramienta básica para evaluar el nivel primario de salud de la población.

Para los diagnósticos de sobrepeso, obesidad e insuficiencia ponderal en edades pediátricas, con grados de sensibilidad y especificidad muy satisfactorios utilizando exclusivamente la antropometría nutricional, se han propuesto diversos indicadores antropométricos que cuantifican la magnitud del tejido adiposo y muscular, con el objeto de identificar situaciones de riesgo o con propósitos de intervención. Entre los más utilizados, tanto en clínica como en estudios poblacionales,a pesar de su limitación en tanto que no identifica masa grasa y masa muscular de manera independiente (1), destaca el índice de masa corporal (IMC),considerado como el instrumento más común de medición en estudios epidemiológicos (2-4). El uso de este indicador en un comienzo estuvo restringido a la evaluación del adulto, pero en tiempos recientes ha sido igualmente recomendado para la valoración de niños y adolescentes (5, 6), ya que el IMC permite estimar los cambios de la adiposidad en la etapa del crecimiento, al presentar una alta tendencia a la canalización (7).

Sin embargo aún con la aceptación de su uso en edades pediátricas, varias investigaciones señalan la necesidad de que en este grupo y para efectos de diagnóstico, el IMC esté acompañado de otros indicadores de composición corporal como el área grasa (AG) y el área muscular (AM)(8,9), especialmente durante la pubertad, ya que durante este período del ciclo vital las diferencias son mayores debido al ritmo o tempo de maduración (10-12).

Aunque parece existir un consenso en la utilización de criterios internacionales para la evaluación del sobrepeso y la obesidad, tanto en niños como en adolescentes, su aplicación continúa siendo motivo de controversia, ante la variabilidad de resultados encontrados de acuerdo con la referencia utilizada (13), diferencias que no pueden ser atribuibles únicamente a la selección de los valores límite de cada referencia (P10 y P90 en la referencia nacional; P15 y P85 en la internacional), sobre todo en aquellos países que cuentan con valores de referencia nacionales que contemplan las particularidades propias de su composición corporal(14, 15).

Ante esta dicotomía, el objetivo de la presente investigación fue evaluar la capacidad del IMC para predecir composición corporal, diagnosticada por AG y por AM, utilizando la referencia nacional (16) en comparación con la referencia internacional (17),en adolescentes de sexo femenino clasificadas según presencia o no de la menarquia.

MATERIALES Y MÉTODOS

Esta investigación es de carácter comparativo y está enmarcada dentro de los objetivos contemplados en la Unidad de Investigación: Bioantropología, Actividad física y Salud (ubafs.ucv) del Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas y Sociales de la Universidad Central de Venezuela. Las participantes en este estudio constituyen una subpoblación de 364 adolescentes femeninas del banco de datos de la mencionada unidad con el siguiente criterio de inclusión: sexo femenino, aparentemente sanas, escolarizadas, con edades comprendidas entre los 10 y 15 años, residentes en zonas de Caracas y del estado Mérida (Venezuela), con registro de presencia/ausencia de la menarquia.

El banco de datos de la unidad contiene información antropométrica, socioeconómica, demográfica y cultural, de maduración somática, menarquia, actividad física y aptitud física, recabada en instituciones educativas provenientes de 5 estudios transversales realizados en varios estados de Venezuela entre los años 2011 al 2015, y con consentimiento informado, en adolescentes desde los 9 años hasta los 18 años de uno y otro sexo. Las investigaciones se llevaron a cabo de acuerdo con las normas deontológicas reconocidas por la declaración de Helsinski (18). En estos cinco estudios las variables antropométricas fueron recopiladas por antropometristas experimentados de acuerdo con los lineamientos de la Sociedad Internacional para el Avance de la Kinantropometría (19); de la siguiente manera: el peso corporal con el sujeto de pie en el centro de la balanza sin apoyo y distribuido equitativamente en ambos pies, empleándose una balanza electrónica portátil -PretitionTech- con gradación cercana a los 100 g. La talla máxima se apreció con un estadiómetro portátil marca Harpenden con escala métrica de 1mm de precisión; se consideró la distancia perpendicular entre los planos transversales entre los puntos del Vertex y el inferior de los pies. El pliegue de tríceps se apreció en la línea media de la cara posterior del brazo que se encuentra con la línea acromialeradiale media proyectada perpendicularmente al eje longitudinal del brazo, para ello se utilizó un calibrador Slim Guide con precisión de 0,5 mm y una presión de cierre constante de 10g/mm2.

Las variables consideradas para este estudio fueron las siguientes: peso en kg (P), talla en metros (T), pliegue tríceps en mm (PlTr), circunferencia media del brazo en cm (CB), edad en años (E) y presencia o no de la menarquia. Con esta información se calcularon los indicadores: índice de masa corporal (IMC), área grasa (AG) y área muscular (AM), mediante las siguientes fórmulas IMC (20); AG y AM (21): Para cada uno de estos tres índices se aplicó un criterio de clasificación en tres categorías (déficit, normal y exceso) utilizando valores de referencia nacionale internacional. Para el caso nacional se usaron las tablas del ENCDH (16). En este sentido se utilizó la siguiente regla basada en los percentiles correspondientes: déficit: <P10, normal: ≥P10 y ≤P90, y exceso: >P90 (22). Para la referencia internacional se utilizaron los nuevos estándares de la OMS para niños y adolescentes entre 5-19 años de edad (17). En este caso la clasificación se sustenta en el siguiente criterio: déficit: <P15, normal: ≥P15 y ≤ P85, y exceso: >P85. La presencia o no de la menarquia derivó dos grupos de adolescentes para el análisis: premenárquicas y menárquicas (23).

MÉTODOS ESTADÍSTICOS

Los procedimientos estadísticos utilizados para comparar el desempeño del IMC como predictor tanto de AG como de AM, según las dos referencias (ENCDH y OMS), consistieron en establecer mediciones de los siguientes cuatro aspectos:

a) Concordancia entre ambas referencias, evaluada en el grupo de niñas con composición corporal normal (según los indicadores AG o AM) y clasificadas de acuerdo con la presencia o ausencia de la menarquia. Para estos efectos se utilizó el coeficiente Kappa-wponderado, pro- puesto por Fleiss y Cohen (24), y definido como: Kappaw = siendo  una medida global del acuerdo entre las dos reglas, determinada como la suma ponderada de las probabilidades estimadas de que el IMC por la primera y segunda referencias clasifiquen simultáneamente a una adolescente en las categorías i y j respectivamente, y

una medida global del acuerdo entre las dos reglas, determinada como la suma ponderada de las probabilidades estimadas de que el IMC por la primera y segunda referencias clasifiquen simultáneamente a una adolescente en las categorías i y j respectivamente, y  una medida global del acuerdo esperado entre las dos reglas, bajo el supuesto de independencia. Para efectos de interpretación se ha convenido en asumir el siguiente criterio para la concordancia: pobre (0,0-0,2), débil (0,2-0,4), moderada (0,4-0,6), buena (0,6-0,8) y muy buena (0,8 -1,0).

una medida global del acuerdo esperado entre las dos reglas, bajo el supuesto de independencia. Para efectos de interpretación se ha convenido en asumir el siguiente criterio para la concordancia: pobre (0,0-0,2), débil (0,2-0,4), moderada (0,4-0,6), buena (0,6-0,8) y muy buena (0,8 -1,0).

b)Precisión del IMC según cada una de las reglas, para clasificar una adolescente en la condición de déficit o de exceso, según su composición corporal, en forma separada para AG y AM. Las medidas de precisión utilizadas fueron la sensibilidad (fracción de verdaderos positivos: FVP) y la especificidad (fracción de verdaderos negativos: FVN), determinándose además las correspondientes fracciones de error: fracción de falsos negativos (FFN) y fracción de falsos positivos (FFP).

c)La capacidad de cada regla para predecir la composición corporal (AG y AM) por déficit o por exceso, evaluada mediante razones de verosimilitud diagnósticas, distinguiéndose además las adolescentes según presencia o no de la menarquia. Las razones de verosimilitud diagnóstica positivas (25) quedan definidas mediante el cociente: DLR+ =cuyos valores mayores que la unidad constituyen un indicativo de que una persona clasificada con déficit o exceso, es más probable que presente esta condición a que no la tenga. También se calcularon razones de verosimilitud diagnósticas negativas definidas en la forma DLR-=, cociente cuyos valores menores que la unidad indican que una persona clasificada como normal, es más probable que realmente lo sea a que presente déficit/exceso.

d) Comparación de la capacidad diagnóstica de ambas reglas. Con este fin se calcularon las razones de verosimilitud diagnósticas relativas, definidas de la siguiente manera: rDLR+ ( IMC_ENCDH, IMC_OMS) = donde sirDLR+>1, entonces una persona clasificada con défict/exceso según IMC_ENCDHes más indicativo que según IMC_OMS, lo que da mayor certeza en la clasificación obtenida por la primera regla, y: rDLR-( IMC_ENCDH, IMC_OMS) = donde sirDLR<1, entonces una persona clasificada como normal según IMC_ENCDHes más indicativo que según IMC_OMS (25).

RESULTADOS

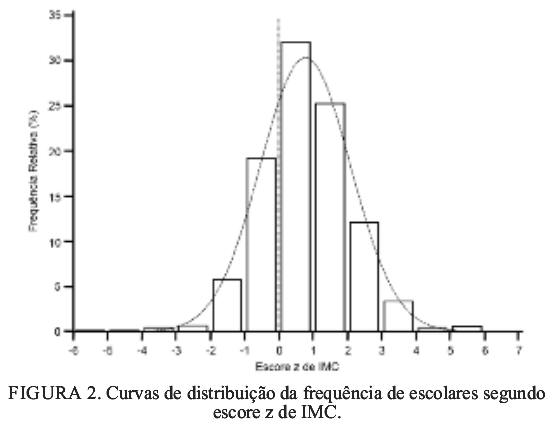

La evaluación de la composición corporal para la gran mayoría de las participantes en el estudio, permitió clasificarlas como normales, tanto en lo que respecta a reservas calóricas medidas por AG (87%), como a las reservas proteicas medidas por AM (74,5%). Asimismo, el IMC correspondiente a un alto porcentaje de estas adolescentes estuvo en la normalidad para la referencia nacional (80%), observándose sin embargo una importante disminución para la referencia foránea (67%) (Figura1). En general, las magnitudes observadas del coeficiente Kappa ponderado en los distintos grupos bajo estudio, indicaron un nivel de moderado a bueno en la concordancia entre los clasificadores IMC_ENCDH e IMC_OMS (Figura 2). Debe destacarse sin embargo, el caso de adolescentes premenárquicas con composición corporal normal según área muscular, en las que la concordancia registrada resulto más bien débil (0,37). Adicionalmente, resalta el hecho de que este coeficiente sea moderadamente más elevado en las adolescentes con composición corporal normal según área grasa, en comparación con las normales de acuerdo al área muscular, independientemente de la ocurrencia de la menarquia.

En la Tabla 1 se muestra que la sensibilidad del IMC_ENCDH para clasificar correctamente el déficit en AG fue relativamente baja, siendo menor en las post-menárquicas (0,43) que en las premenárquicas (0,56). Por consiguiente, las fracciones de error al clasificar un déficit como normal fueron muy altas: 57% en las menárquicas y 44% en premenárquicas. Cabe resaltar además que comparativamente esta referencia tiene un mejor desempeño en la predicción del exceso que del déficit, tanto en pre como en post-menárquicas. Por su parte, la precisión del IMC_OMS para clasificar correctamente tanto el déficit (sensibilidad: 0,57 a 0,67) como el exceso (sensibilidad: 0,84 a 0,92), fue muy superior a la de la referencia nacional, independientemente de la ocurrencia de la menarquía, mostrando también un mejor desempeño para la predicción del exceso. Se encontró en general que la referencia nacional fue más específica que sensible tanto para el déficit como para el exceso, lo que hizo que las fracciones de error resultaran pequeñas en la clasificación de adolescentes normales. Un comportamiento similar se observó para la referencia foránea, solamente en el caso de déficit.

FIGURA 1. Distribución porcentual de las adolescentes según categorías de los indicadores de composición corporal y nutricional.

En la predicción del área muscular, las dos referencias diagnósticas evidenciaron un comportamiento análogo al del área grasa (Tabla 2). En todas las situaciones bajo estudio, el IMC_OMS siempre fue más sensible que IMC_ENCDH. Con respecto al mejor desempeño de las dos referencias para la predicción del exceso, en relación a la correspondiente al déficit, esto solamente se observó en las adolescentes premenárquicas. En cuanto a la especificidad, el IMC_ENCDHsiempre resultómás específico que sensible, condición que en la referencia foránea solo fue evidente para el déficit.

Las verosimilitudes diagnósticas positivas (DLR+) obtenidas para ambas referencias fueron todas mayores que la unidad (3,60 a 34,67) (Tabla 3). Estos resultados constituyen un indicativo de que un diagnóstico de composición corporal de acuerdo al AM o AG en las dos categorías de déficit o exceso basado en el IMC, resultó al menos tres veces más probable que proviniera de una adolescente con una alteración real, que de una normal. Este hallazgo se evidenció con mayor intensidad para el IMC_ENCDH como predictor del área muscular en premenárquicas, tanto para el déficit como para el exceso. Por su parte, las verosimilitudes diagnósticas negativas (DLR-) según las dos referencias, resultaron todas menores que la unidad (0,09-0,61).

Esto significa que en el caso de diagnosticar una adolescente como normal es más probable que su composición corporal (AM o AG) sea normal a que no lo sea (Tabla 4). En este sentido destaca en importancia el caso de IMC_OMS como predictor del área grasa en las adolescentespremenárquicas para la categoría diagnóstica de exceso, es decir, si una persona ha sido clasificada como normal por IMC_OMS, sería poco probable que su condición diagnóstica estuviera en la categoría de exceso.

Las Figuras 3 y 4 permiten señalar que para predecir alteraciones de la composición corporal por déficit o por exceso mediante el IMC en las adolescentes menárquicas, resultó indistinto recurrir a la referencia nacional o a la foránea ya que los valores no difieren sustantivamente de la unidad. Sin embargo, en el caso de adolescentes premenárquicas, se encontró que la referencia nacional era más indicativa que la foránea, tanto en el diagnóstico del déficit según área muscular [rDLR + (ENCDH,OMS) =4,83] como del exceso [rDLR+(ENCDH,OMS)=3,09]. Mención aparte merece el caso de predicción de normalidad según área grasa, en el cual la referencia foránea tuvo un mejor desempeño que la nacional [rDLR-(ENCDH,OMS)= 2,82].

DISCUSIÓN

A nivel mundial se han llevado a cabo diversas reuniones de expertos para consensuar distintos criterios técnicos y metodológicos, en torno al uso e interpretación de los indicadores antropométricos en la investigación científica y en la definición de políticas de salud de niños y adolescentes, relacionadas con el estado nutricional de este grupo poblacional. Esta tarea es de particular importancia cuando la acción está dirigida a la identificación de grupos de riesgo o evaluar los resultados de programas de salud.

En este artículo se analizaron las diferencias y/o similitudes en el comportamiento del IMC por las referencias nacional e internacional para predecir el estado nutricional antropométrico de un grupo de adolescentes, evaluado en términos de su composición corporal con base en los componentes de área grasa y área muscular, utilizando los valores límite recomendados para cada caso. Adicionalmente, se consideró la presencia o ausencia de la menarquia como un factor importante para evaluar los resultados de la predicción.

Los primeros hallazgos revelaron diferencias en la identificación de adolescentes normales utilizando el IMC por una u otra referencia, encontrándose que la referencia internacional reportó una menor prevalencia en lo que corresponde al estado nutricional normal.

En general el nivel de concordancia observado entre las referencias diagnósticas osciló entre moderado y bueno, con una excepción en el grupo de premenárquicas con área muscular normal, en las que el comportamiento de las reglas es discordante. Este hallazgo debe llamar la atención ya que en una investigación realizada en una muestra longitudinal de Caracas, se encontró que a diferencia del área grasa, el componente muscular por su parte presentaba diferencias según el ritmo o tempo de maduración (26).Una explicación parcial de este último hecho estriba en que el IMC por la referencia nacional es más específico que sensible tanto para la predicción de área grasa como de área muscular, y en consecuencia induce un menor riesgo de error en la clasificación de niños normales. Por el contrario, en general el IMC foráneo es más sensible que específico, lo que conlleva a un menor riesgo de error en la clasificación de la malnutrición en general. Este comportamiento de las reglas queda manifiesto también en las razones de verosimilitud diagnósticas positivas, siempre mayores en ENCDH que en OMS. Estas comparaciones, que seresumen en las razones de verosimilitud relativas, llevan a concluir que en las adolescentespremenárquicas la referencia ENCDH es más indicativa de déficit/exceso en área muscular que la OMS,mientras que esta última es más indicativa del exceso en área grasa en adolescentes premenárquicas.

La comparación de las referencias diagnósticas ENCDH y OMS realizadas en este estudio, pueden permitir ser de utilidad en la toma de decisiones más eficientes en la focalización e intervención de esta problemática dirigida a la población adolescente. Esta eficiencia se traduce en la escogencia de la referencia diagnóstica apropiada, ya que una clasifica mejor a los normales y la otra mejor a la malnutrición. Además se encontró que la referencia nacional es más indicativa que la foránea para la reserva proteica en el grupo de adolescentes premenárquicas.

Aun cuando para este trabajo no se evaluaron los caracteres sexuales secundarios (glándulas mamarias y vello pubiano), algunas de las adolescentes clasificadas como premenárquicas podrían mostrar un comportamiento similar al encontrado en las menárquicas; puesto que la menarquia es un evento relativamente tardío dentro del periodo puberal.Estas diferencias son consistentes con otros estudios reportados por la OMS, en los cuales la estimación de las prevalencias de sobrepeso y obesidad están influenciadas por la selección de la población, ya que éstas tienden a pertenecer a muestras de niños y adolescentes eutróficos, es decir personas con un estado nutricional evaluado por antropometría, dentro de los parámetros considerados normales (27).

Las diferencias encontradas derivadas del evento de la menarquia en este grupo de estudio, revela la importancia de la selección en el uso del estándar nacional o internacional, el cual debe ser tomado en consideración para valorar el grado de déficit o exceso nutricional. Se ha llegado a conclusiones similares en estudios realizados en poblaciones belgas, norteamericanas y venezolanas, basados en los diferentes grados de maduración, los cuales inciden en modificaciones de la composición corporal que alteran a su vez, la valoración del estado nutricional (28-31). Por otra parte, queda demostrado que los niveles de concordancia del IMC varían de acuerdo al componente objeto del análisis, ya sea que se refiera al graso o muscular, encontrándose coincidencias más relevantes cuando se trata del primero.

Estos resultados vendrían a fortalecer la propuesta de Atalah y colaboradores (32), en cuanto a la necesidad de retomar mesas de trabajo para dilucidar el tema del uso de referencias locales versus internacionales, ya que las diferencias encontradas así lo justifican.

CONCLUSIONES

Los hallazgos obtenidos en esta investigación permiten concluir que en adolescentes con composición corporal normal según AG, se observaron niveles de concordancia entre ambas referencias, similares para los dos grupos. En las adolescentes con composición corporal normal según el AM, se observó mayor concordancia entre ambas referencias en las menárquicas que en laspremenárquicas. La predicción tanto del déficit como del exceso es más confiable con la referencia ENCDH que con la OMS, con resultados más relevantes en las adolescentes premenárquicas; sin embargo, es oportuno mencionar, que la referencia nacional resultó menos convincente que el de la referencia OMS como predictor de la condición de normalidad. En general, el IMC_OMS es levemente menos específico que el IMC_ENCDH.

AGRADECIMIENTOS

Los autores dejan constancia de su agradecimiento al Consejo de Desarrollo Científico y Humanístico de la Universidad Central de Venezuela, institución que mediante el financiamiento de varios proyectos de investigación, ha permitido la construcción de una base de datos en el área de la biología humana.

REFERENCIAS

1. Bergman RN, Stefanoski D, Buchanan TA, Summer AE, Reynolds JC, Sebringn, et al. A better index of body adiposity. Obesity 2011; 19(5):1083-1089. [ Links ]

2. zimmermann MB, Gübeli C, Püntener C, Molinari L. Detection of overweight and obesity in a national sample of 6–12-y-old Swiss children: accuracy and validity of reference values for body mass index from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the International Obesity Task Force 1, 2, 3. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 79(5): 838-843. [ Links ]

3. Cole TJ, Flegal KM, Nicholls D, Jackson AA. Body mass index cut offs to define thickness in children and adolescents: international survey. BMJ 2007; 335(7612): 194-201. [ Links ]

4. Pérez BM, Landaeta-Jiménez M, Amador J, Vásquez M, Marrodán MD. Sensibilidad y especificidad de indicadores antropométricos de adiposidad y distribución de grasa en niños y adolescentes venezolanos. Interciencia 2009; 34(2): 84-90. [ Links ]

5. Malina RM, Katzmarzyk PT. Validity of the Body Mass Index as an indicator of the risk and presence of overweight in adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr 1999; 70(Suppl.2): S131-S136. [ Links ]

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Child&Teen BMI. Disponible en: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html [Consultado: 20 de febrero de 2015].

7. Inocuchi M, Matsudo N, Takayama H, Hasegawa T. BMI z score is the optimal measure of annual adiposity change in elementary school children. An Hum Biol 2011; 38(6): 747-751. [ Links ]

8. Marrodán MD, Pérez BM, Morales E, Santos-Beneit G, Cabañas MD. Contraste y concordancia entre ecuaciones de composición corporal en edad pediátrica: aplicación en población española y venezolana Nutr Clin Diet Hosp 2009; 29(3): 4-11. [ Links ]

9. Fariñas Rodríguez L, Vázquez Sánchez V, Martínez Fuentes AJ. índice de Masa Corporal y composición del brazo en niños cubanos.Rev Cubana Invest Biomed 2014; 33(4):374-380. [ Links ]

10. Eveleth P. Valores de referencia. En: M López-Blanco, Y Hernández-Valera , B Torún, L Fajardo (eds.). Taller sobre Evaluación Nutricional Antropométrica en América Latina. Ediciones CAVENDES. Caracas 1995; pp.13-19. [ Links ]

11. López-Blanco M, Espinoza I, Macías-Tomei C, BlancoCedres I. Maduración Temprana. Factor de riesgo de sobrepeso y obesidad durante la pubertad?. Arch Latinoam Nutr 1999,49(1):13-19 [ Links ]

12. Macías-Tomei C, López-Blanco M, Blanco-Cedres L, Vásquez- Ramírez M. Patterns of body mass and muscular components in children and adolescents of Caracas. Acta Med Auxol 2001; 33(3):139-144. [ Links ]

13. Kain J, Uauay R, Vio F, Albalá C. Trends in overweight and obesity prevalence in Chilean children: Comparison of three definitions. Eur J Clin Nutr 2002; 56(3): 200204. [ Links ]

14. Júliusson PB, Roelants M, Hoppinbrowers K, Hauspie R, Bjerknes R. Growth of Belgian and Norwegian children compared to WHO growth standards: prevalence below -2 and above +2SD and the effect of breastfeeding. Arch Dis Child 2011; 96(10): 916-921. [ Links ]

15. Milani S, Buckler JMH; Keinar CJH, Benso L, Gilli G, Nicoletti I, et al. The use of local reference growth charts for clinical use or universal standard: a balanced appraisal. J. Endocrinol Invest 2012; 35(2): 224-226. [ Links ]

16. Méndez Castellano H. Estudio Nacional de Crecimiento y Desarrollo Humanos de la República de Venezuela. Proyecto Venezuela. H. Méndez Castellano (editor). Escuela Técnica Popular Don Bosco. Tomo II. Caracas 1996; 846 p. [ Links ]

17. World Health Organization. Growth Reference Data for Children from 5 to 19 Years, Geneva 2007. Disponibleen: www.who.int/growthref/en / . [Consultadofebrero 2015].

18. World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. 64th WMA General Assembly. Fortaleza, Brazil 2013. [Consultadofebrero 2015].

19. Protocolo Internacional para la Valoración Antropométrica.A. Stewart, M.Marfell-Jones, T. Olds, H. de Ridder (Editores). Publicado por ISAK. Biblioteca Nacional de Australia 2011; 112 p. [ Links ]

20. Keys A, Fidanza F, Karvonen MJ, Kimura N, Taylor HL.Indices of relative weight and obesity.J ChronDisease1972; 25(6-7): 329-343 [ Links ]

21. Gurney JM, Jelliffe DB. Arm anthropometry in nutritional assessment: nomogram for rapid calculation of muscle circumference and cross-sectional muscle and fat areas. Am J Clin Nutr 1973; 26(9): 912-915 [ Links ]

22. Landaeta-Jiménez M, López-Blanco M, Méndez Castellano H. Arm muscle and arm fat areas: reference values for children and adolescents. Project Venezuela. Auxology 94 Humanbiol Budapest. 25: 555-561, 1994.

23. Macías de Tomei C. Evaluación de la maduración Sexual. En: M. López, I. Izaguirre, C. Macías (editoras). Crecimiento y MaduraciónFísica. Editorial MédicaPanamericana. Caracas 2013, pp. 153-161.

24. Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measures of reliability. EducPsycholMeas1973; 33(3): 613-619. [ Links ]