Interciencia

versión impresa ISSN 0378-1844

INCI v.29 n.12 Caracas dic. 2004

Prediction of goat litter size using body measurements

Miguel Mellado, José E. García, Rogelio Ledezma and Jesús Mellado

Miguel Mellado. Doctor, Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro (UAAAN), Mexico. Professor, UAAAN, Mexico. Dirección: Departamento de Nutrición. UAAAN. Buenavista s/n, Saltillo, Coah. 25315 México. e mail: mmellbosq@yahoo.com

José E. García. M.C., UAAAN. Mexico. Professor, UAAAN, Mexico. e-mail: egarcia@uaaan.mx

Rogelio Ledezma. Doctor, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León (UANL), Mexico. Professor, UANL, Mexico. e-mail: ledesma210470@hotmail.com

Jesús Mellado. M.C., UAAAN, México. Professor, UAAAN, Mexico. e mail: chuymellado@aol.com

Resumen

El cambio de la circunferencia abdominal, el peso corporal y la distancia vulva-cervix fueron utilizados para predecir el número de fetos de cabras en agostadero. El incremento de peso de las cabras durante la gestación fue de 5,49 ±2,3 y 6,9 ±2,9kg (media ±error estándar) para las cabras con uno o dos fetos, respectivamente. El incremento en la circunferencia abdominal fue de 9,3 ±2,9 y 10,6 ±3,3cm para cabras con uno o dos fetos, respectivamente. Al final de la preñez la distancia vulva-cervix fue de 3,0 ±1,6 y 3,3 ±1,2cm para cabras con uno o dos fetos, respectivamente. Los análisis discriminatorios de mediciones corporales de 97 cabras mostraron que entre 68 y 90 días de preñez, el cambio de peso de las cabras fue la variable más adecuada para separar las cabras según el número de fetos, acertándose en el 62% de las cabras con gestaciones múltiples. Entre los días 91 a 114 de gestación la circunferencia abdominal permitió identificar dos tercios de las cabras con dos fetos. Entre los 115 y 142 días de preñez, el peso vivo de las cabras fue la variable más confiable para predecir el número de fetos de las cabras. En todos los estadios de gestación la distancia vulva-cervix fue la variable menos precisa para distinguir a las cabras de acuerdo al número de sus fetos. Con la combinación de las mediciones corporales indicadas se incrementó muy poco la precisión para predecir el número de fetos de las cabras. Se concluye que el cambio en la circunferencia abdominal alrededor del día 100 de gestación puede predecir con moderada exactitud el número de fetos de cabras gestantes en condiciones de agostadero.

Summary

Changes in abdominal circumference (total and right half), live weight and vulva-cervix distance were used to predict the number of fetuses under range conditions. Total body weight gain during gestation was 5.49 ±2.3 and 6.9 ±2.9kg (mean ±standard error) for single and twin-bearing does, respectively. The increment in abdominal circumference was 9.3 ±2.9 and 10.6 ±3.3cm for single and twin-bearing does, respectively. At the end of pregnancy the vulva cervix distance was 3.0 ±1.6 and 3.3 ±1.2cm for single and twin-bearing does, respectively. Discriminant analyses on records of 97 goats indicated that at 68-90 days of pregnancy, live weight change was the best predictor variable, with 62% being correctly classified as twin-bearing does. At 91-114 days of gestation abdominal circumference on average identified two thirds of twin-bearing does. At 115-142 days of pregnancy live weight gain was again the best predictor variable for separation of does according to number of fetuses. In all stages of pregnancy, the vulva-cervix distance was an erratic variable for discriminating between single-and twin-bearing does. Little precision in predicting litter size was gained by combining pairs of variables. It is concluded that change in abdominal circumference at around 100 days of gestation is of moderate practical significance for predicting multiple fetuses in goats under field conditions.

Resumo

A mudança da circunferência abdominal, o peso corporal e a distância vulva-cervix foram utilizados para prever o número de fetos de cabras em refúgios de verão. O incremento de peso das cabras durante a gestação foi de 5,49 ± 2,3 e 6,9 ± 2,9kg (media ± erro estandar) para as cabras com um ou dois fetos, respectivamente. O incremento na circunferência abdominal foi de 9,3 ± 2,9 e 10,6 ± 3,3cm para cabras com um ou dois fetos, respectivamente. No final da gestação à distância vulva-cervix foi de 3,0 ± 1,6 e 3,3 ± 1,2cm para cabras com um ou dois fetos, respectivamente. As análises discriminatórias de medições corporais de 97 cabras mostraram que entre 68 e 90 dias de gestação, a mudança de peso das cabras foi a variável mais adequada para separar as cabras segundo o número de fetos, acertando-se em 62% das cabras com gestações múltiplas. Entre os dias 91 a 114 de gestação a circunferência abdominal permitiu identificar dois terços das cabras com dois fetos. Entre os 115 e 142 dias de gestação, o peso vivo das cabras foi a variável mais confiável para prever o número de fetos das cabras. Em todos os estágios de gestação, a distância vulva-cervix foi a variável menos precisa para distinguir às cabras de acordo ao número de seus fetos. Com a combinação das medições corporais indicadas incrementou-se muito pouco a precisão para prever o número de fetos das cabras. Conclui-se que a mudança na circunferência abdominal ao redor do dia 100 da gestação pode prever com moderada exatidão o número de fetos de cabras gestantes em condições de refúgios de verão

KEYWORDS / Abdominal Circumference / Goats / Litter Size / Live Weight /

Received: 09/03/2004. Modified: 11/11/2004. Accepted: 11/12/2004.

Introduction

In small ruminants, nutritional status is very important during the last trimester of pregnancy for both mother and fetuses (Holst et al., 1992). Therefore, detection of the number of fetuses is of economic value to the goat industry, because it allows appropriate nutritional management of goats with multiple fetuses.

A number of methods are available to detect fetal numbers in small ruminants, among which ultrasonography (real-time, B-mode) is currently the most reliable, safe, and commercially practical method under field conditions (Fowler and Wilkins, 1984; Davey, 1986; Gearhart et al., 1988; Hallford et al., 1990; Schrick and Inskeep, 1993). However, the initial cost of equipment and the operator skill and experience that is required makes general use of ultrasonography prohibitive for commercial goat operations under range conditions in developing countries. Hormone analysis is also a tool for predicting fetal numbers. Ewes carrying twins have about twice the concentration of progesterone as ewes carrying single lambs (Schneider and Hallford, 1996; Manalu and Sumaryadi, 1998; Khan and Ludri, 2002; Muller et al., 2003). Pregnancy-specific protein B (Hallford et al., 1990) and pregnancy-associated glycoprotein (Batalha et al., 2001) have also been used to estimate fetal numbers in small ruminants. Again, the cost of kits and equipment, and operator skills, are limiting factors to these methods for diagnosis of fetal numbers in resource-poor goat operations.

Detection of fetal numbers in small ruminants by rectal-abdominal palpation is a quick, simple and cheap, but inaccurate technique (Hulet, 1973; Chauhan et al., 1991). Besides, the risk of rectal damage (bruising, abrasion or perforation) with the palpating road, and the occurrence of abortion and death in sheep (Turner and Hindson, 1975; Tyrrell and Plant, 1979) and goats (Ott et al., 1981) is relatively high, which makes this procedure unattractive for goat owners. Because of the need of a simple, reliable, safe and cheap diagnostic technique for detecting number of fetuses in goats under extensive conditions, a technique of body measurements was investigated as an alternative method for litter size diagnosis in goats. This was based on the fact that, in contrast to other ruminants, pregnant does present a marked abdominal expansion in late gestation.

Materials and Methods

Site description and goat management

The study was carried out in a rural community settlement in Northeast Mexico (25º14N and 101º10W). The climate is semiarid with annual precipitation averaging 320mm. Seventy percent of the total annual precipitation falls from June to October. The average annual temperature is 18.2ºC, and mean elevation is 1700m. The study area vegetation is characterized as Chihuahan desert rangeland. Crossbred goats (Criollo x dairy breeds) of different ages, guided by a herdsman, foraged exclusively on native vegetation for approximately 8h daily (from 10:00 to 18:00) and spent the night in an unroofed pen made of branches. Goats did not receive supplemental feed and had no health intervention. Does were field mated during 4 weeks in January for June kidding.

Experimental procedure

Goat body weight, total abdominal circumference, right half-abdominal circumference (from the umbilical scar to the third lumbar vertebra) and vulva-cervix distance were recorded in 97 mixed-breed does of all ages every 21 days, starting at the end of the breeding period. Body measurements were recorded with a flexible measuring tape, and the vulva-cervix distance was determined with the plastic sheath of an insemination gun, with a measuring scale placed internally. This sheath was gently introduced into the vagina until resistance was encountered. This sheath was cleaned, dipped in an antiseptic solution, and lubricated with a water soluble gel after each measurement. Kiddings, abortions and litter size were recorded. Gestation length was assumed to be 150 days; thus, the interval between date of parturition and date of measurements gave the stage of pregnancy at each measurement.

Statistical methods

Discriminant analyses (SAS, 1989) were carried out using the following variables at different stages of pregnancy: body weight, complete abdominal circumference, half abdominal circumference (right side) and vulva-cervix distance. Linear regressions were used to describe the association between days of gestation and body measurements. Tests of heterogeneity of regression were made to detect differences between goats bearing single or twin fetuses.

Results

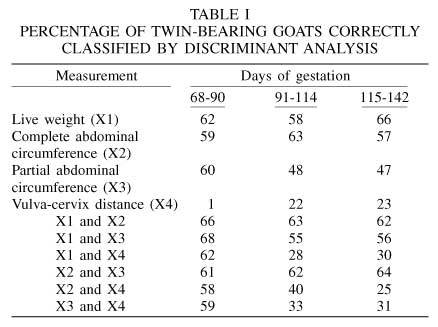

The results of discriminant analyses for individual and combined variables are presented in Table I. At 68-90 days of pregnancy live weight change was the most effective single variable for identifying twin-bearing does. At 91-114 days of gestation complete abdominal circumference distinguished with moderate accuracy the goats carrying twins (63% were correctly classified). At 115-142 days of gestation live weight change was again the best single variable for identifying does carrying twins, increasing precision by 4 percent points over that achieved by the same variable at 68-90 days of gestation. In all stages of pregnancy very little precision in predicting fetal numbers was gained by combining pairs of variables to predict fetal numbers.

The relationship between days of pregnancy and live weight change during gestation is illustrated in Figure 1. Weight of twin-bearing does started to increase at day 52 of gestation, whereas weight of single-bearing does started to increase at 59 days of pregnancy. Total body weight gain during gestation was 5.49 ±2.5 and 6.87 ±2.9kg (mean ±standard deviation) for single and twin-bearing does, respectively. For the complete abdominal circumference, the test for heterogeneity of slopes and intercepts between single and twin-bearing does revealed that regression coefficients were constant over groups. Therefore, a single regression line was used to describe the association between this variable and days of pregnancy (Figure 2). From day 55 of gestation until kidding the abdominal circumference showed a steady expansion with a total increment of 9.3 ±2.9 and 10.6 ±3.3cm for single and twin-bearing does, respectively.

In addition, a single regression line was indicated for the association between partial abdominal circumference and time of gestation. In this case, the right part of the abdomen started to expand at 55 days of gestation, with a total increment of 5cm at the end of gestation, for both single and twin-bearing does (Figure 2). Different to other body measurements, the vulva-cervix distance in pregnant does began to increase after day 60 of gestation (Figure 3). At the end of pregnancy the cervix was 3.0 ±1.6cm and 3.3 ±1.2cm deeper in single and twin-bearing does, respectively.

Discussion

Live weight was superior to all other body measurements for discriminating between goats carrying one or two fetuses at the middle and end of gestation. At 68 to 90 days of pregnancy the increment in weight would, on average, correctly classify 62% of pregnant does, which closely agree with data of Burton et al. (1990) in ewes. At this stage of gestation the accuracy of this method to diagnose fetal numbers is close to the rectal abdominal palpation technique (Hulet, 1973; Chauhan et al., 1991; Sandabe et al., 1994) and slightly lower than those of plasma progesterone concentrations (Gadsby et al., 1972) and plasma pregnancy-specific protein B (Willard et al., 1995). Thus, in order to identify two thirds of twin-bearing does, the increment in body weight should be checked after day 115 of pregnancy (in extensive systems, 3.5 months after the end of a 30 days breeding period). Considering that the greatest fetus development occurs in the last trimester of gestation, detecting the number of fetuses at this time of pregnancy would allow enough time to adjust nutrient intake of twin-bearing does before parturition.

During the present study the availability of food throughout the gestation period was exceptionally good, which resulted in a 19% increment in the body weight of pregnant does. Typically, this is not the case in Northeast Mexico, where weight gain of pregnant does is normally limited or a body weight loss can occur, in which case abortion may take place (Mellado et al., 2001). Thus, as indicated in other studies (Richardson, 1972), live weight increment after breeding would not always be a reliable indication of pregnancy or fetal numbers under range conditions.

At 91 to 114 days of gestation the increment in abdominal circumference would identify two thirds of the twin bearing goats. Thus, this approach seems to be the most adequate among the methods tested, because abdominal scoring is fast and does not require equipment or experienced operating staff. At this stage of gestation the increment in abdominal circumference for single and twin-bearing does was 5.8 ±2.6 and 6.5 ±2.8cm, respectively. For practical purposes, the following steps (Burton et al., 1990) would be necessary to predict the number of fetuses: 1) estimate the percentage of does that are likely to bear twins (e.g. for the present study 47% of the pregnant does had twins); 2) determine the abdominal circumference of pregnant does to set a cut-off point "x" such that 47% of does have scores greater than "x"; 3) separate the flock into two groups, with abdominal circumferences greater and less than "x". If more than 47% of does goes to the group with higher scores, the cut-off point "x" should be increased, if less, "x" should be decreased.

In classifying the twin-bearing does throughout gestation, the vulva-cervix distance was an ineffective method. Besides, this technique requires that the sheath used for measurements be cleaned, dipped in an antiseptic solution and lubricated after each measurement, which is difficult to be performed by goat owners under resource-poor conditions.

Conclusions

This study determined that the increment in abdominal circumference at around 100 days of pregnancy is a simple, rapid, practical and safe technique for separation of single- and multiple-bearing does. However, it would be expected that only two-thirds of does would be correctly classified with this technique under farm conditions. A follow-up study whereby pregnant does would not have access to the acceptable nutritional level at which the does in the present study were, is warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Appreciation is extended to COECYT (grant number COAH-2002-C01-3753) for funding of this study.

REFERENCES

1. Batalha ES, Sulon J, Figueiredo JR, Beckers JF, Martins GA, Silva LDM (2001) Relationship between maternal concentrations of caprine pregnancy-associated glycoprotein in Alpine goats and the number of fetuses using a homologous radioimmunoassay. Small Rumin. Res. 42: 105-109. [ Links ]

2. Burton RN, Saville DJ, Bray AR, Moss RA (1990) Prediction of ewe litter size using udder scores, liveweights, and condition scores. N.Z. J. Agr. Res. 33: 41-48. [ Links ]

3. Chauhan FS, Sandabe UK, Oyedipe EO (1991) Predicting numbers of fetus(es) in small ruminants. Indian Vet. J. 68: 751-754. [ Links ]

4. Davey CG (1986) An evaluation of pregnancy testing in sheep using real-time ultrasound scanner. Aust. Vet. J. 63: 347-348. [ Links ]

5. Fowler DG, Wilkins JF (1984) Diagnosis of pregnancy and number of the fetuses in sheep by real-time ultrasonic imaging: 1. Effect of number of fetuses, stage of gestation, operator and breed of ewe on accuracy of diagnosis. Liv. Prod. Sci. 11: 437-450. [ Links ]

6. Gadsby JE, Heap RB, Powell DG, Walters DE (1972) Diagnosis of pregnancy and of the number of fetuses in sheep from plasma progesterone concentrations. Vet. Rec. 90: 339-341. [ Links ]

7. Gearhart MA, Wingfield WE, Knight AP, Smith JA, Dargatz DA, Boon JA, Stokes CA (1988) Real-time ultrasonography for determining pregnancy status and viable fetal numbers in ewes. Theriogenology 30: 323-337. [ Links ]

8. Hallford DM, Ross TT, Oetting BC, Sachse JM, Heird CE, Sasser RG (1990) Estimation of fetal numbers in ewes using ultrasound or serum concentrations of progesterone or pregnancy-specific protein B. Proc. West Sec. Am. Soc. Anim. Sci. 41: 380. [ Links ]

9. Holst PJ, Allan, CJ, Gilmour AR (1992) Effects of a restricted diet during mid pregnancy of ewes on uterine and fetal growth and lamb birth weight. Austr. J. Agr. Res. 43: 315-324. [ Links ]

10. Hulet CV (1973) Determining fetal numbers in pregnant ewes. J. Anim. Sci. 36: 325-330. [ Links ]

11. Khan JR, Ludri, RS (2002) Hormonal profiles during periparturient period in single and twin fetus bearing goats. Asian - Australasian J. Anim. Sci. 15: 346-351. [ Links ]

12. Manalu W, Sumaryadi MY (1998) Maternal serum progesterone concentration during gestation and mammary gland growth and development at parturition in Javanese thin-tail ewes carrying a single or multiple fetuses. Small Rumin. Res. 27: 131-136. [ Links ]

13. Mellado M, González H, García JE (2001) Body traits, parity and number of fetuses as risk factors for abortion in range goats. Agrociencia 35: 355-361. [ Links ]

14. Muller T, Schubert H, Schwab M (2003) Early prediction of fetal numbers in sheep based on peripheral plasma progesterone concentrations and season of the year. Vet. Rec. 152: 137-138. [ Links ]

15. Ott RS, Barun WF, Lock TF, Memon MA, Stowater JL (1981) A comparison of intrarectal Doppler and rectal abdominal palpation for pregnancy testing in goats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 178: 730-731. [ Links ]

16. Richardson C (1972) Pregnancy diagnosis in the ewe: A review. Vet. Rec. 90: 264-275. [ Links ]

17. Sandabe UK, Chauhan FS, Chaudhri SUR, Wiziri MA (1994) Studies on predicting number of foetus(es) in small ruminants. Pakistan Vet. J. 14: 97-100. [ Links ]

18. SAS (1989) SAS Users Guide. SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, NC, USA. 505 pp. [ Links ]

19. Schneider FA, Hallford DM (1996) Use of a rapid progesterone radioimmunoassay to predict pregnancy and fetal numbers in ewes. Sheep Goat Res. J. 12: 33-38. [ Links ]

20. Schrick FN, Inskeep EK (1993) Determination of early pregnancy in ewes utilizing transrectal ultrasonography. Theriogenology 40: 295-306. [ Links ]

21. Turner CB, Hindson, JC (1975) An assessment of a method of manual pregnancy diagnosis in the ewe. Vet. Rec. 96: 59-61. [ Links ]

22. Tyrrell RN, Plant JW (1979) Rectal damage in ewes following pregnancy diagnosis by rectal abdominal palpation. J. Anim. Sci. 48: 348-354. [ Links ]

23. Willard JM, White DR, Wesson CAR, Stellflug J, Sasser RG (1995) Detection of fetal twins in sheep using radioimmunoassay for pregnancy-specific protein B. J. Anim. Sci. 73: 960-966. [ Links ]

uBio

uBio