Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Archivos Latinoamericanos de Nutrición

versión impresa ISSN 0004-0622versión On-line ISSN 2309-5806

ALAN v.51 n.1 supl.1 Caracas mar. 2001

The use of sugar fortified with iron tris-glycinate chelate in the prevention of iron deficiency anemia in preschool children

Regiane A. Cardoso de Paula, Mauro Fisberg

São Marcos University- São Paulo, Brazil

SUMMARY.

In the present work, the effectiveness of consumption for 6 months of iron fortified sugar in the prevention or control of iron deficiency anemia was evaluated in 93 children (10-48 months old) attending a day care center in São Paulo, Brazil. Each child consumed 20 g of fortified sugar per day for 5 days a week in orange juice during breakfast.Two levels of fortification were tested using iron tris-glycinate chelate as the source of iron. Level one sugar contained 10 mg of iron /kg of sugar, and level 2, 100 mg of iron/kg. The children were assigned to either of the two groups. The first group (n=42) received level 1 sugar, and those of group two (n=52) received level 2 sugar. The daily iron intake corresponded to 2 and 20% of the RDA. At the end of the 6 months trial period, significant increases in weight/height ratio was observed in both groups. In the group consuming level 1 fortified sugar the mean change in hemoglobin concentration was 0,4 g/dL (from 11,3 grams to 11,7 g/dL), and in the group consuming level two fortified sugar the mean hemoglobin increase was also 0,4 g/dL (from 11,6 to 12,0 g/dL). Both changes were highly significant (p<0.00l). When only the anemic children were considered (32/93), the increment of hemoglobin was 1,4g/dL. In anemic children there was a significant increase in the levels of serum ferritin. The increase was more notorious in group 2 children. We verified that the acceptability of the iron-fortified sugar was excellent. There were no detectable changes in the organoleptic characteristics of the fortified sugar as compared with unfortified sugar. No differences in response were observed between the two groups indicating that probably the lower level of iron was absorbed more efficiently that the higher level. The iron tris-glycinate chelate was very well tolerated with no side effects registered. It was concluded that even with low iron levels, the consumption of iron fortified sugar is an effective, low cost intervention for the control and prevention of iron deficiency anemia in preschool children.

Key words: Ferrochel, sugar fortification, effectiveness of iron fortified sugar, iron deficiency anemia control.

RESUMEN.

El uso de azúcar fortificado con hierro tris-glicinato quelado en la prevención de anemia ferropriva en preescolares. En el presente estudio se evaluó la efectividad del consumo por 6 meses de azúcar fortificado con hierro tris-glicinato quelado en la prevención o control de anemia ferropriva en niños preescolares. Un total de 93 niños atendiendo una centro de cuidado diario fueron estudiados. Se utilizaron dos niveles de fortificación. En el nivel 1 el azúcar fue fortificado con 10 mg de hierro /kg de azúcar. y en el 1 nivel 2 con 100 mg de hierro /kg. Los niños se distribuyeron en dos grupos. Grupo 1 (42 niños) consumió azúcar con el nivel 1 de fortificación. El grupo dos (52 niños) consumió azúcar con el nivel 2 de fortificación. En ambos grupos el azúcar fortificado fue usado por 5 días a la semana en jugo de naranja administrado durante el desayuno. El jugo de naranja contenía 20 de azúcar. Al final de los 6 meses del estudio ambos grupos mostraron incrementos significativos en la razón peso/talla y un incremento medio de hemoglobina de 0.4 g/dL. Esta diferencia fue altamente significativa (p>0.00l). Cuando el incremento en hemoglobina de los niños con anemia (32/93) fue analizado, este incremento fue de 1,4 g/dL. Dado que ambos grupos tuvieron un incremento igual en hemoglobina se postula que la absorción del hierro en dosis bajas es mas alta. En niños anémicos hubo un incremento significativo en la concentración de ferritina en suero. Se pudo verificar que no hubo ningún cambio en las características organolépticas del azúcar fortificado, y que este fue excelentemente tolerado por todos los niños. Se concluye que el azúcar fortificado con hierro tris-glicinato quelado puede ser un medio efectivo de controlo prevención de anemia ferropriva en niños preescolares.

Palabras clave: Ferrochel,. fortificación de azúcar, efectividad de azúcar fortificado con hierro, control de anemia ferropriva.

INTRODUCTION

Iron deficiency (ID) is a major public health concern due to its high prevalence and to the side effects it brings to the health of affected population groups. Many factors contribute to the high prevalence of ID in underdeveloped countries, among then, poor diets, diarrhea, intestinal infections and intestinal parasites (1-4). All these factors significantly contribute to children morbidity (3).

There are many non-hematological effects of ID, such as decrease capacity for physical activity, and alterations in the learning process and in motor and mental development. ID also has a depressing effect on cellular immunity, resulting in increased susceptibility to infection (5-7).

The high prevalence of ID makes it mandatory to seek new interventional strategies to control de deficiency (3).

Studies carried out by the World Health Organization (WHO), have shown that ID is a major cause of health related disorders, and decreased work capacity leading to significant economic loss in many populations. In the United States, 15-20% of the population under 18 years of age, suffers from ID, while in developing countries up to 51% of the population is affected (5,8).

In Brazil, important changes in the nutritional status of the population have taken place in the last few decades. There has been a gradual reduction in child mortality rates, a decrease in the total prevalence of protein-energy malnutrition, especially of the chronic forms, but at the same time, the prevalence of iron deficiency has increased (8,9).

Data from regional studies has shown that the high prevalence of iron deficiency anemia is a national concern, affecting all social groups, but predominantly in the most deprived population.

During the 80s, in the northeastern part of the country, anemia prevalence was 20-75% in preschool children, (depending on the studied region (9,10). In the Amazon region, approximately 50% of the preschool children population suffered from this disease (11,12). In the Southern regions, where there is a high consumption of beef-based food, Turconi and Turconi (13), found that in the Municipality of Bento Gonçalves, 37.4 % of children aged 0-12 months suffered from anemia, and that in the Federal District of Brasilia, in a study of 279 children below 36 months of age attending public day-care centers the prevalence was 28.7% (14).

In 1978, in the city of Sao Paulo, Sigulem, et al, found an anemia prevalence of 22% in children up to 5 years of age (15), and ten years later, Montero and Szarfac, studying a similar population, found that anemia prevalence had increased to 35,7% (16). In 1992, the São Paulo State Health Agency, in a study that covered several areas of the State, found a prevalence of 59,1 % in infants that attended the Basic Health Units (13,15,16). In another study, part of the National Survey of Malnutrition and Anemia, carried by the Nutritional and Health Research Center of São Marcos University in preschool children, it was found that in the city of São Paulo, with the best economic indexes in the country, the prevalence of anemia was up to 75% in children below 5 years of age (14). All these reports made it mandatory to start iron supplementation and food fortification programs considered to be the most appropriate measures to control the deficiencies.

The major technical difficulty in planning a fortification program is the selection of the iron compound to be used. When choosing the iron compound, the organoleptic alterations of the food vehicle, its bioavailability and its market price have to be evaluated (8,24,37). The ideal food vehicle is regularly consumed by the target population in predictable amounts.

The fortification of foods with iron is the most effective measure to control the deficiency in a population. With this strategy, it is possible to reach all socioeconomic groups (8).

Ferrous sulfate is the most frequently used iron salt, but other salts such as ferrous fumarate and lactate can also be used, although at a higher cost. Sodium iron EDTA (NaFeEDTA) has been used in sugar fortification in Guatemala and in wheat flour in Egypt with limited success (18,8).

The development of more physiological iron chelates, such as iron bis- and tris-glycinate chelates opens new possibilities in food fortification, because of its higher bioavailability and its lack of alteration of the organoleptic characteristics of the selected foods (17,18). With these compounds, several types of foods have been tested in the last decade such as milk, sugar, bread, cookies, grains and salt (18-23,38).

In Brazil, several studies in food fortification with iron have been carried out in the last decade in an effort to find a viable way of controlling iron deficiency in the population. In 1994, Fisberg, et al, were able to show that three months consumption of "petit Suisse" cheese fortified with iron bis- glycinate chelate resulted in a significant decrease in anemia prevalence in preschool children (24).

In 1995, Torres, et al, evaluated the impact of the consumption of powdered cow's milk fortified with iron bis- glycinate chelate on anemia prevalence of preschool children. The study carried out under the auspices of the State of Sao Paulo Health Agency established that consumption for one year of fortified milk, significantly reduced the prevalence of IDA in the studied population (17).

In the city of Barueri, 1296 children ranging in age from 6 months to 6 years were studied. Eight hundred and ninety six of these children aged 4-6 years received bread fortified with 2 mg iron from the bis-glycinate chelate, and 400, aged 6 months to 3 years received cookies fortified with the same amount of chelated iron. At the end of the study it was found that the children that consumed fortified bread had a mean increase in hemoglobin of 0.74 g/dL, and those consuming the fortified cookies 0.72 gidL (25).

In the present study we tested the effectiveness of the consumption of sugar fortified with either 10 or 100 mg of iron per kg from iron tris-glycinate chelate (a taste free iron chelate), on the iron nutritional status of preschool children. At the time of the study, sugar fortified with 10 mg iron per kg was available in the Brazilian market. We also studied the effect of a tenfold increase in the iron fortification level.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A day care center from a Public Institution was chosen for the study. The sample was conformed by 93 children aged 10 to 48 months distributed in two groups. A pediatrician carried out physica1 examinations of all the chi1dren. The following factors were analyzed: c1inica1 characteristics and signs re1ated to previous and current diseases, anthropometry, and hematological condition. The pediatrician was in charge of supervision and training of the personne1 invo1ved in the intervention program. In two of the chi1dren in the samp1e no anthropometric data was collected due to their frequent absence at the time of gathering the data.

At the beginning of the intervention and six months after, all the children were subjected to c1inical examination, anthropometric measurements and 1aboratory tests. All children with hemoglobin levels < 9,0 g/dL were exc1uded from the study, treated with ferrous su1fate and controlled by the pediatrician of the project. During the observation period, no changes were made in the diet of the day-care center, except for the use of sugar fortified with iron tris-glycine che1ate as a sweetener in the orange juice ingested by the chi1dren. Children that fai1ed to attend the day-care center for more than 10 consecutive days or 18 nonconsecutive days were excluded from the statistical analysis.

Blood samp1es were collected by venipuncture on a peripheral vein using discardable materials. Hemoglobin and ferritin determinations were carried out at the beginning and end of the study (6 months). Hemoglobin was measured by automated procedures (26), and serum ferritin by radioimmunoassay (27). Children were considered anemic when their hemoglobin levels were < 11 g/dL (28), and iron deficient when their serum ferritin leve1s were les s than10 m g/L (8,27,29).

Data on weight and height was col1ected at the beginning and end of the tria1. A digita1, portable scale with capacity for 150 kg with 50 g divisions was used. Children were weighed naked or wearing the minimum amount of clothes possible, when weather was a concern. Estimates of the anthropometric ratios weight for age (W/A), height for age (H/A) and weight for height (W/H) were calculated using the program EPI - INFO 6,04 (CDC, Atlanta, GA, U.S.A.). The calculated z-score distribution was compared with WHO reference standard s (30).

Each child received 20 grams of sugar fortified with either 10 mg of iron /kg of sugar (group 1), or 100 mg of iron /kg of sugar, both in orange juice. The iron used in the fortification was iron tris-glycinate chelate (Albion Laboratories, Inc. Clearfield, Utah, U.S.A.). This is a taste-free compound. The ingested fortified sugar provided 2% ROA of iron for group 1 and 20% ROA for group 2.

The comparison of the results in the two groups was carried out using parametric and nonparametric statistics. Student "t" test and two-way analysis of variance for a fixed significant level of 5% (31-33).

RESULTS ANO DISCUSSION

The use of a staple food as a vehicle for iron fortification has always been the goal of researchers all over the world. The fortified food should be consumed by every risk group in a continuous and controlled way, and should have low price. Thus, milk, flours, salt and others are being used for this purpose.

Sugar is, in fact, a natural option, for it fills the described characteristics. The use of ferrous salts in sugar deeply alters its organoleptic characteristics preventing its use. This problem, was overcome by the use of iron tris-glycinate chelate since it produces only very slight variations in the physical characteristics of sugar and no organoleptic change.

This intervention using iron-fortified sugar is only the second world's trial and the first to overcome the organoleptic problems. Sugar fortified with 10 mg of iron from the amino acid chelated per kg was already available in the Brazilian market. Sugar fortified with 100 mg iron I kg of sugar was specifically prepared for this study.

Table I shows the anthropometric characteristics of the population studied.

Anthropometric characteristics of the children enrolled in the study

| Group | Age, months mean ± S.D. (Range) | Weight, Kg mean ± S.D. (Range) | Height, cm mean ± S.D. (Range) |

| 1

2 P* | 29,2±9,5 (11,7-40,8) 31,4±10,0 (10,4-44,8) n.s | 12,9±2,2 (9,2-17,5) 13,7±2,4 (9,1-18,7) n.s | 89,2±8,1 (73,0-102,5) 91,7±9,0 (71,5-103,4) n.s |

Students "t" test for independent samples

It is noteworthy that in the present study the acceptability of the fortified sugar was excellent regardless of the iron dose used. There was no detectable change in taste in the orange juice, or side effect due to the use of the fortified sugar.

At the beginning of the study, the selected population presented a prevalence of anemia of 33.3%. This value was lower than that previously obtained by Torres, et al, (17), but very similar to the values previously obtained in the cities of Barueri (34,35) and Brasilia (14).

In the present study, despite the low level of iron added to the sugar (2 and 20% RDA), a mean increase in hemoglobin levels, of 0.40 g/dL in the six-month 1 consumption period was observed in both groups. This increase is very close to that obtained in a similar time with milk fortified with this same iron chelate. Studies conducted by us and several other groups have shown that even with higher fortification levels in milk, the increase in hemoglobin in a six-month period is about 0.5 g/ dL. (17,19,).

After the intervention with iron-fortified sugar, there was a mean decrease in the prevalence of anemia of 43.8% for group 1, which received the lower dose of iron, and of 66.7% for group 2. The total mean prevalence of anemia, came down from 33.3 to 18.3%. (Table 2).

Effect of intervention on the prevalence levels of low hemoglobin levels

| Group |

| Hb basal N (%) | Hb post Tx N (%) | Prevalence Change (%) |

| 1 2 Total | <11 =11 <11 =11 <11 | 16 (38,1) 26 (61,9) 15 (29,4) 36 (70,6) 31 (33,3) | 7 (16,7) 35 (83,3) 10 (19,6) 41 (80,4) 17 (18,3) | -43,8 +34,6 -66,7 +13,9 -54,8 |

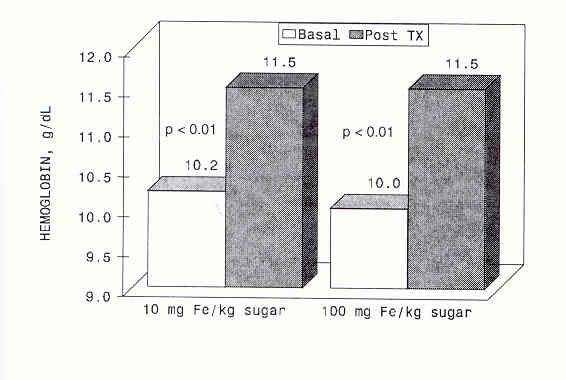

If only anemic children are analyzed, the increase in hemoglobin values obtained in the six months period of sugar consumption is 1.3 g/dL for group 1 and 1.5 g/dL for group 2. These results are highly significant, with the advantage that they can be achieved with a much lower cost and with no side effects (35). Moreover, the mean hemoglobin 1evel reached normal values in both groups, with no significant difference between the groups (Figure 1).

Effect of 6 months consumption of 20 g of fortified sugar per day on hemoglobin levels

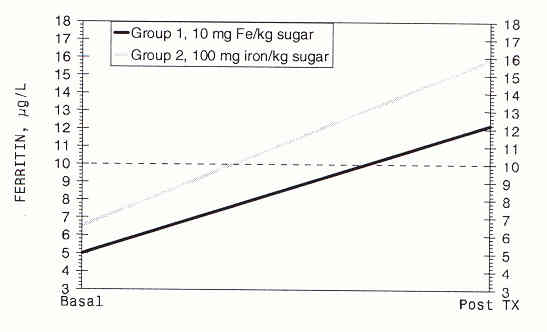

In the group, as a whole, there was no significant change in body iron reserves as measured by serum ferritin levels. Most probably, the period of intervention with levels of iron that are a small fraction of the RDA was not long enough to alter iron reserves. However, when children with iron deficiency at the beginning of intervention were analyzed, there was a significant increase in ferritin from 5,0 to 12,2 m g/L for group 1 and from 6,5 to 15,9 m g/L for group 2 (Figure 2). This shows a trend toward normalization of ferritin values in children with iron deficiency (36).

Effect of 6 months consumption of 20 g/day of iron fortified sugar on serum ferritin levels of iron deficient children

The trend towards increasing hemoglobin and ferritin levels of the chi1dren studied, do not seem to be re1ated to the dose of iron used. This may be a reflection of the small doses used, since even with a fortification leve1 of 100 mg iron per kg of sugar, the iron contribution in the dose taken represents only 20% of the iron RDA, and it is a know phenomenon that at low levels, iron is absorbed more.

When assessing the anthropometric results of only those children considered at nutritional risk at the beginning of the trial, only group 1 presented a significant progress for the weight/height ratio. The biologically meaning of these results may not have any important significance because of the short time of treatment. There was no relationship between anemia prevalence and nutritional status, probably due to the general adequate nutritional leve1 of the population at the beginning of the trial.

As it was already mentioned, sugar is considered a staple food, with low cost, that can be easily distributed for popultions at risk. Several studies have shown that its adequate use is not related to increase in prevalence of obesity or tooth decay (18,36).

The search for an effective iron compound with good bioavailability and of universal application has been the objective of worldwide research (5). The results obtained in this study show that the use of iron tris-glycinate chelate to fortify sugar is an extremely useful altemative for the control of iron deficiency anemia.

The fortification of sugar with iron trís-glycinate chelate is very satisfactory in preventing iron deficiency anemia. There is no detectable alteration in the flavor or in the organoleptic characteristics of sugar. There is a very slight change in color that does not prevent its acceptance in OUT day-care center. However, after months of storage of the fortified sugar, there was a tendency for the formation of dark or yellowish dots in the inner part of the packaging. This may affect the commercial aspect of the product, but does not modify the good results obtained in the present trial. We have to point out that the sugar used in Brazil is very white and powdered. For general crystallized sugar fortification, the necessary technology has been developed considering the specific characteristics of local sugar to prevent these changes from happening.

The trial using sugar fortified with iron tris-glycinate chelate resulted in a significant increase in hemoglobin levels and in a reduction in anemia prevalence. There was no observable dose related effect, maybe because of the very low relative doses of iron used. As expected from an absorption and regulation point of view, the effects were evident only in children who presented anemia at the beginning of the trial.

No side effects were encountered during the duration of the trial with either level of sugar fortification. On the contrary, there was an excellent tolerability and acceptance. We conclude, therefore, that sugar fortified with iron trís-glycinate chelate in low doses, is an effective means in preventing iron deficiency anemia in populations at risk.

REFERENCES

1. Burton B. Nutrição Humana. Ed. Mac Graw Hill, São Paulo, 1979;434-445. [ Links ]

2. Committee on Nutrition . Iron Supplementation. Pediatrics 1979; 58:765-8. [ Links ]

3. Lozoff B, Jimenez B, Wo1f AW. Long Term Developmental Outcome of Infants with Iron Deficiency. N Eng1 J Med 1991;94: 325:687. [ Links ]

4. Pollit E. Effects of a Diet Deficient in Iron on the Growth and Development of Preschool-age Chi1dren. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 1991;13:110-17. The United Nations University. [ Links ]

5. World Health Organization. Nutritional Anemias. Technical Report Series No. 405. Geneva,1968. p 37. [ Links ]

6. Walter T, Andraca I, Chadud P. Iron Anemia: Adverse Effects on Infant Psychomotor Development. Pediatrics 1989;84;,07-

7. Lozoff B. Has Iron Defficiency been show to Cause Altered Behavior in Infants? In: Brain behavior and iron in the infant diet. Ed. J. Dobbing ,107-1 3 1.,-Spring Verlag, London ,1990. [ Links ]

8. DeMaeyer EM. Preventing and Controlling Iron De ficiency Anaemia Tthrough Primary Health Care. WHO, Geneva, 1989. [ Links ]

9. Instituto Nacional de Alimentação Nutrição. Ministerio de Saúde. Pesquisa Nacional sobre Saúde e Nutrição. Perfil de Crescimiento da População Brasileira de O a 25 anos. Brasilia, 1990, p 60. [ Links ]

10. Braga, JAP. Avaliação do Estado Nutricional de Pré-Escolares submetidos a Intervenção com um Suplemento Lácteo Fortificado com Ferro. Doctorate thesis presented to Universidade Federal de São Paulo, 1996. [ Links ]

11. Salzano AC, Torres MAA, Batista FO, Romani SA. Anemia em Crianças em Dois Serviços de Saúde de Recife, PE (Brasil). Rev. Saúde Pública 1985; 19: 499-507. [ Links ]

12. Silva NB, Maeinho HA, Castro JS, Rocha, YR, Ferraroni MJR Prevalência da Anemia Ferropriva em Crianças Pré- escolares da Cidade de Manaus, AM. Anais: I Congresso Nacional da SBAN, São Paulo, 1988. p.63. [ Links ]

13. Turconi SJ, Turconi VL. Anemia Ferropriva: Incidência em uma População Infantil. Pediatr Mod 1992;28:107-12. [ Links ]

14. Schimits BAS, Aquino KKCN, Picanço MR, Bastos J. Giorgini E, Cardoso R, Braga JAP, Fisberg M. Prevalência da Desnutrição e Anemia em Pré- escolares de Brasilia, Brasil. Pediatr Mod 1998;34:155-64. [ Links ]

15. Sigulem DM, Tudisco ES, Goldenberg P, Athaide MMM. Vaisman E. Anemia Ferropriva em Crianças do Município de São Paulo. Rev. Saúde Púbica 1978;12:168-78. [ Links ]

16. Monteiro CA, Szarfarc SC. Estudo das Condições de Saúde das Crianças do Municipio de São Paulo. S.P. (Brasil), 1984- 1985. Rev. Saúde Publica 1987;21:255- [ Links ]

17. Torres MA, Sato K, Lobo NI, Queiroz SS. Efeito do Uso de Leite Fortificado com Ferro e Vitamina C sobre Níveis de Hemoglobina e Condição Nutricional; de Crianças menores de 2 anos. Revista de Saúde Pública 1995;29:301-7. [ Links ]

18. Viteri FE, Alvarez E, Batres R, Torún B, Pineda O, Mejia LA, Sylvi J. Fortification of Sugar with Iron Sodium Ethylendiaminotetraacetate (FeNaEDTA) Improves Iron Status in Semirural Guatemalan Populations. Am J Clin Nutr 1995;61:1153-6. [ Links ]

19. Queiroz SSQ, Torres MAA. Anemia Carencial Ferropriva: Aspectos Fisiopatológicos e Experiencia com a Utilização do Leite Fortificado com Ferro. Pediatr Mod 1995;31:441-5. [ Links ]

20. Layrisse M, Marinez- Torres C, Renzi M, Velez F, Gonzales M. Sugar as Vehicle for Iron Fortification. Am J Clin Nutr 1976;29:8-18. [ Links ]

21. Calvo E, Hertrampf E, Pablo S, Amar M, Stekel A. Haemoglobin-fortified cereal: an Alternative Weaning Food with High Iron Availability. Eur J Clin Nutr 1989;43:237- 243. [ Links ]

22. Tuntawiroon M, Sritongkul N, Rossander-Hulten L. Pleehachinda R, Suwanik R, Brune M, Hallberg L. Rice and Iron Absorption in Man. Eur J Clin Nutr 1990;44:489-97. [ Links ]

23. Peña GG, Pizarro F, Hertrampf DE. Aporte del hierro del pan a la dieta Chilena. Rev Med Chile 1991;119: 753-57. [ Links ]

24. Fisberg M, Braga JAP, Kliamca PE, Ferreira AM, Berezowski. Utilizção de Queijo "petit suisse" na Prevenção de Anemia Carencial Ferropriva em Pré - escolares. JAMA,- Peediatria 1995;2:14-24. [ Links ]

25. Fisberg M, Velloso EP, Ribeiro RMS, Zulla M, Braga JAP, Soraggi C, Kliamca PE, Chedid EA, Schuch M, Valle J, Cardoso R, Krumfli M, Graziani E. Projeto Barueri Pediatria Atual 1998:11:19-26. [ Links ]

26. Abbott Cell Dyn. Operator Manual. Abbott Diagnostics Operation Reference Manual for Cell - Dyn 3000 - Hematology Analyser 1989, Sequoia -Turner Corporation, California, USA. [ Links ]

27. Franco CD.- Ferritin. In: Kaplan LA and Pesce, A J., Eds. Methods In Clinical Chemistry, 1980, p 124-42. [ Links ]

28. Dallman PR, Reeves JD. Laboratory Diagnosis of Iron Deficiency. In: Stekel A. Iron Nutrition in Infancy and Childhood. (Nestlé Nutrition Workshop Series, No. 4). Raven Press, New York, 1984. [ Links ]

29. Oski FA, Honig A. The Effects of Therapy on the Developmental Scores of Iron Deficient infants. J Pediatr 1978;21:92. [ Links ]

30. Dean AG, Dean JA, Burton AH, Dieker RC. Epi - Info, Version 5.0: A Word Processing, Database, and Statistics Program for Epidemiology on Micro - Computers. Center for Disease Control. Atlanta, GA 367 p., 1990. [ Links ]

31. Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ. Biometry: the Principles and Practice Statistics in Biological Research. Chapter 7: Estimation and Hypothesis Testing. 124-174. Chapter 11: Two-Way analysis of Variance. W. H. Freeman and Co., 1969. [ Links ]

32. Siegel S. Estatística não-paramétrica (para as ciências do comportamento). Cap. 6: Amostras independentes. McGraw - Hill,Brasil, 1975. [ Links ]

33. Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical Methods. 7th edition, The Iowa State University Press, 1982. [ Links ]

34. Fisberg M, Velloso EP. Barueri Project.-Programa de Intervenção Nutricional coro Farinhas Enriquecidas com Ferro para Pré-escolares. Anais do Encontro Estadual sobre Alimentação do Escolar, 1997. P 45-50. [ Links ]

35. Fisberg M, Velloso EP, Ribeiro RMS, Zullo, M, Braga JAP, Soraggi C, Kliamca PE, Chedid EA, Schuch M, Valle, Cardoso R, Krumfli M, Graziani E. Projeto Barueri. Pediatria Atual 1998; 11: 19-26. [ Links ]

36. Vega-Franco L. Deficiência de Hierro en la Infancia: Manisfestaciones Clinicas, Tratamento y Prevencion. Parte II. Bol Med Hosp Inf Mex 1989;46:690-95. [ Links ]

37. Cook JD, Reusser ME. Iron Fortification: An Update. Am J Clin Nutr 1983 38: 648-59. [ Links ]

38. Fisberg M, Pellegrini JAP, Cardoso R, Giorgini E. Uso do pão fortificado com ferro aminoácido quelato em Pré- escolares de 4-6 anos em Barueri SP. Anais XII Congresso Latino Americano de Gastroenterologia Pediátrica e Nutrição, São Paulo, Brasil, 15-19 de Julho, 1996. Abstract 73,104. [ Links ]