Interciencia

versión impresa ISSN 0378-1844

INCI v.29 n.2 Caracas feb. 2004

Rural planning in Costa Rica

Carlos J. Álvarez, Francisco Maseda, Manuel F. Marey and Rafael Crecente

Carlos José Álvarez. Doctor in Agronomical Engineering, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM), Spain. Director, Department of Agriculture and Forestry Engineering, Universidad de Santiago de Compostela (USC), Spain. Address: Escuela Politécnica Superior. Campus Universitario. 27002 Lugo, Spain. e-mail: proyca@lugo.usc.es

Francisco Maseda. Doctor in Agronomical Engineering, UPM, Spain. Director, Centro de Desarrollo Sostenible, Xunta de Galicia, Spain.

Manuel Francisco Marey. Doctor in Forestry Engineering, USC, Spain. Professor, Department of Agriculture and Forestry Engineering, USC, Spain.

Rafael Crecente. Doctor in Agronomical Engineering, USC, Spain. Professor, Department of Agriculture and Forestry Engineering, USC, Spain.

Resumen

Se presentan los resultados de la labor realizada por un equipo de la Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, España, en colaboración con profesores de la Maestría en Desarrollo Rural de la Universidad Nacional de Heredia, Costa Rica, que parte de la finalidad inicial de formular una candidatura para constituir una Cátedra UNESCO de Desarrollo Rural a implantar en la región Huetar Norte de Costa Rica. Una vez analizada la situación, se propone y justifica la creación de un Centro de Planificación y Desarrollo Rural, definido como agente de desarrollo, que supere las limitaciones existentes en la actualidad. Este agente permitirá tres tareas fundamentales: recoger información en calidad y cantidad suficiente para la realización de un diagnóstico preciso de la zona problema, diseñar actuaciones y propuestas concretas de desarrollo totalmente coordinadas entre si, y realizar la labor de seguimiento y gestión de las actuaciones, evaluando su incidencia y adecuándolas a las nuevas realidades que se vayan presentando. La propuesta se considera totalmente exportable a otros países en vías de desarrollo.

Summary

This paper describes the results of a study undertaken by a team of rural development experts from the University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain, in collaboration with academic staff of the Masters Programme in Rural Development of the National University at Heredia, Costa Rica, with the view to draft a proposal for the creation of a UNESCO Chair in Rural Development in the Costa Rican region of Huetar Norte. Following appraisal of the current situation in this region, it was concluded that a Regional Development Planning Center should be created to support the teaching and research activities of the proposed Chair and integrate them with the activities of a unit devoted to the collection and analysis of the data needed for regional planning in Huetar Norte, and to the formulation, facilitation and monitoring of development plans for this region. The proposed model is regarded as totally generalizable to other developing countries.

Resumo

Este artigo descreve os resultados do estudo efectuado pelos especialistas de Engenharia Rural da Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Espanha, com. a colaboração de professores do Masters Programme em. Desenvolvimento Rural da Universidade Nacional de Herédia, Costa Rica. Visa a elaboração de uma proposta para a criação de uma "UNESCO Chair"em. Desenvolvimento Rural na região Huetar Norte, na Costa Rica.. Após a apreciação da situação actual nesta região, concluye-se que deve ser criado um Centro de Planeamento de Desenvolvimento Regional, para suportar o ensino e a investigação da "Chair" proposta e integrá-los nas actividades de uma unidade especializada na a recolha e análise dos dados necessários para o planeamento regional em Huetar Norte, e para formular, facilitar e monitorizar os planos de desenvolvimento para esta região. Espera-se que o modelo proposto seja totalmente generalizado aos outros países em desenvolvimento.

KEYWORDS / International Cooperation / Rural Development / UNESCO Chair /

Received: 09/29/2003. Accepted: 02/03/2004.

As a contribution to the efforts of Spain and of the Spanish autonomous community of Galicia to promote the development of Latin America, in 1997 the University of Santiago de Compostela formulated the suggestion that a UNESCO Chair in Rural Development be created in the underdeveloped Costa Rican region of Huetar Norte, a suggestion that in 1999 received the support of the Compostela Group of Universities. The detailed preparation of the project fell to the authors of this paper, who knew little about Costa Rica and nothing about Huetar Norte. The first task was therefore to become familiar with the territory in question, but the initial search of the literature revealed that there were no relevant systematic regional inventories of the kind that are customary in Europe. In view of this, it was concluded that for the proposed UNESCO Chair to produce the intended social benefits it would be necessary to create a regional planning agency capable, among other things, of acquiring the basic data that would be required for the activities of the Chair. Therefore, a proposal was drafted for the establishment of a Regional Development Planning Center (RDPC) that would not only act as the institutional context of the planned UNESCO Chair, supporting its teaching and research activities, but would also gather data, perform diagnosis and planning, and otherwise facilitate the rural development of the region.

In December 2001 the Chair application was submitted to UNESCO headquarters by its Costa Rican National Commission, and is currently under review. In this paper we describe the development of the RDPC proposal sketched above.

Background

Geographical context: Central America

The Central American isthmus is a narrow bridge linking North and South America and lying between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. It is a region of high tectonic and volcanic activity, and on a geological time scale has undergone numerous climatic changes. Biologically, it has channeled the exchange of species between North and South America, and has developed a rich biodiversity.

The population of the region has grown rapidly from about 11 million in 1950 to 35 million in 2000 (MIDEPLAN, 1998), with an average density of 65 inhabitants per km2. A large proportion of the population is accordingly composed of young people anxious for education and training. In spite of intense migration from rural to urban areas (De Janvry and Sadoulet, 2000), which with current economic difficulties are no longer able to absorb new immigrants (Reinhardt and Peres, 2000), about 50% of the population is still rural.

As is well-known in Europe, where land redistribution schemes have been put in practice both to denationalize State-owned property in Eastern Europe and to regroup the disperse properties of small farmers in countries such as Spain (Crecente et al., 2002), land ownership is a crucial issue for rural development. The legacy of the colonial history of Central America includes the ownership of a large proportion of the land by a very small number of landowners. This is undoubtedly a contributory cause of only about 51% of land being used rationally, 27% being over-exploited and 22% under-exploited (MIDEPLAN, 1996). The practical impossibility of the acquisition of land by the non-landowning peasantry is a prime cause of the poverty that is general among this sector of the population: 60% of Central Americans suffer poverty, 40% are in extreme poverty, and in the age of globalization there are few signs of significant improvement in their situation in the foreseeable future, in spite of the efforts of numerous governmental and international agencies and NGOs (Korzeniewicz and Smith, 2000). In the last years rural Americas economy, culture, and landscape have entered a period of sustained and dramatic change (Marcouiller et al., 2002). Among other causes of rural economic precariousness that should be tackled in a coordinated fashion (Pérez, 1999) is included the destruction of natural resources by over-exploitation and the enhancement, due to under-exploitation, of the risk of their destruction by natural causes or others (Hyde and Kohlin, 2000); both these processes are themselves consequences of the lack of coordinated regional planning systems that would allow integrated, balanced resource management.

Costa Rica

Compared to other Central American countries, Costa Rica has a long democratic tradition and relatively high levels of education and professional expertise, particularly in fields relevant to rural development. About 56% of the population live in rural areas, and the farming sector has traditionally played a central role in social and economic development; in 1998 it contributed 18% of the gross national product, 73% of exported value and, directly or indirectly, 21% of new jobs (MIDEPLAN, 1998). In the case of Costa Rica, state interventionism in agriculture has benefited both production and the rural population (Colburn, 1993), but 50% of the rural population nevertheless suffers poverty, and socioeconomic indices reflect disadvantage with respect to urban areas (Fernández et al., 1999). The infrastructural deficits that hamper the development of the nation are particularly marked in rural areas (MIDEPLAN, 1998), and the high immigration rate endangers the provision of basic services and calls for rapid, effective application of mechanisms of social integration (MIDEPLAN, 1996). The environmental and ecological wealth of the nation (Costa Rica possesses between 4 and 6% of world biodiversity; MIDEPLAN, 1997) is threatened, as elsewhere in Latin America, by deforestation and other destructive processes, and requires the implementation of measures for its conservation and management (Holl et al., 2000).

Costa Ricas current development strategy aims at sustainable development satisfying the social and economic needs of the population in harmony with the environment (Fallas, 1993), and it is one of the worlds top-ranked countries in this field. The development and competitiveness of rural areas is currently being promoted by modernization of the structure and legal status of relevant organizations and institutions. This facilitates international cooperation, and rural development is in fact being pursued with a relatively high level of collaboration by international organizations in the fields of research, education and coordination.

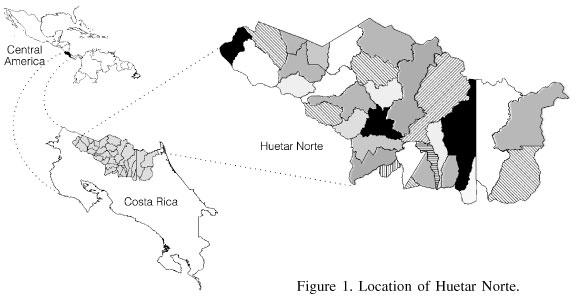

Huetar Norte

Figure 1 shows the location of the region of Huetar Norte. Socioeconomic indices show it to be one of the most depressed rural areas of Costa Rica (it has the third highest regional prevalence of poverty, and is one of the four regions with employment rates below the national average) and that it also suffers marked intraregional inequalities (MIDEPLAN, 1998). Its development is hampered or threatened, inter alia, by conflicts over land use, environmental degradation, the over-dependence of the economy on the primary sector, marketing problems, poor management and coordination of governmental agencies, and deficient information systems. In the Costa Rican governments development plans it is a priority area; in particular, the cantons of Upala, Los Chiles, Guatuso and Sarapiquí have top priority for intervention.

Rural development

Rural development may be regarded as a type of social change in which new ideas are introduced in a social system with a view to achieve higher per capita productivity and standards of living through modern methods of production and improved social organization (Knickel and Renting, 2000). It is a complex process in which all the mutually interacting factors involved must be taken jointly into account. Planning for rural development consists in studying the area in question with a view to the design of a project aimed at improving the standard of living and quality of life of its inhabitants and, on the basis of such study, design a project for the exploitation of endogenous resources and of any available exogenous resources in a way that is rational and sustainable, increases the number of jobs, improves existing ones, and improves infrastructures and services, thus advancing towards the future without loss of social cohesion and identity (Van der Ploeg, 2000).

Development plans should coordinate the objectives of all parties involved, endeavouring to harmonize the interests of citizens, business and government, with government leading the process and communicating the development area with the outside world so as to link it into the global economic networks that are the basis for any development program (Murdoch, 2000).

The design of a development plan requires a prior study of the territory to be developed (Tourino et al., 2003). This involves characterization of its production, social conditions, internal economy and external economic environment, especially in the case of areas subject to programmes of international aid, which will generally be decisive for the validity of the plan (North and Cameron, 2000). This study will be the basis for specific strategic proposals as to how to realize potential and correct deficiencies, proposals that should be devised in the light of the experience of other territories so as to exploit ways of promoting coordinated development that have proved successful in improving the quality of life of citizens (Van der Ploeg and Renting, 2000).

A development plan should also include a time schedule and contemplate short-, medium- and long-term actions and their coordination with other programmes that are being applied in the area at various levels of government, or application of which is planned. Finally, continuous monitoring of the efficacy of the plan is essential for dynamic management to be able to modify planned courses of action in the light of changing reality (Steiner et al., 2000).

UNESCO Chairs

The UNESCO Chairs programme was approved by the General Conference of 1991. It is UNESCOs most novel initiative in the field of higher education, but has become a key aspect of the Organizations activity in this field. Its objective is to strengthen worldwide international cooperation in higher education through the creation of teaching and research programmes fitted to the beneficiary countries specific needs of sustainable development. It is based on two fundamental themes: rapid transfer of knowledge and information, and aid for the institutional development of higher education. By March 1999, 340 Chairs and 50 networks of participating universities had been established in a wide range of fields (including sustainable development, environment and population, science and technology, social sciences and humanities, peace, democracy and human rights), with emphasis on multidisciplinary approaches. The program is aimed at universities and other centers of higher education that are recognized as such by their relevant national authority.

The process of creation of a UNESCO Chair begins with the submission of a detailed project that is evaluated by the appropriate technical committee of the UNESCO Secretariat. A chair may be created in order to establish a new teaching or research unit in a university or other center of higher education or research center; or to carry out an existing programme of teaching or research in an existing university department.

After analyzing the situation of Huetar Norte, the creation of a Regional Development Planning Center (RDPC) was proposed. It would not only act as the institutional context of the planned UNESCO Chair, supporting its teaching and research activities, but would also constitute an agency for the development of the region.

Analysis of the Situation of Huetar Norte

The analysis comprised three stages:

- A review of the published literature and other available documents providing information that would allow to identify and delimit the chief economic sectors and their interrelationships, and to draw up a preliminary list of persons to be interviewed.

- Diagnosis of the internal strengths and weaknesses and external opportunities and threats of the main sectors on the basis of the information obtained in the previous stage, interviews with persons involved in the development of the region, and direct field observations.

- Global diagnosis of the planning situation.

Initial diagnosis

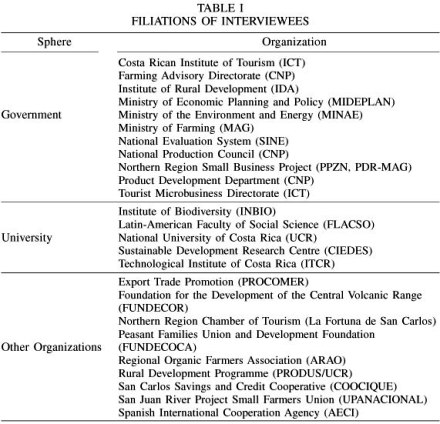

As noted in the Introduction, the literature and other documentation on Huetar Norte turned out to provide insufficient information for proper analysis of the relevant economic sectors. To supplement this deficiency, inventory campaigns were carried out at various times during the years 1999, 2000 and 2001, in collaboration with the Masters Programme in Rural Development of the National University at Heredia, Costa Rica. Interviews covered persons belonging to national, regional and local government, official organizations, private enterprise, NGOs, community associations, cooperative societies, and other entities involved in the development of the region (Table I). These interviews were very helpful, but not surprisingly failed to provide the quantitative census data that had not been provided by official statistics, and the results of our own observational field work were likewise illuminating but insufficient.

Almost all those interviewed agreed in pointing to farming, forestry and tourism as the three sectors of greatest current and future importance and growth potential. In general, all three were deficient as regards information and statistics, infrastructure, institutional coordination, regional planning, marketing, access to factors of production, and research; and were in a reasonably healthy situation as regards the availability of natural resources and qualified labour, the involvement and support of rural communities and national and international organizations, and the enactment of beneficial legal reforms. Note that, because of their importance for all other sectors, key rural development activities such as infrastructure provision are not treated here as independent sectors but are instead included in the characterization of each of the three sectors mentioned above.

Global diagnosis of the planning situation

As indicated already, the data available on Huetar Norte in the literature and other documentation is unsystematic and partial, having been acquired largely in unrelated studies of individual areas and topics; no systematic inventories of the whole region have been carried out. Though suggestive, the available data are therefore insufficient for proper diagnosis of the situation of the region. In fact, the persons interviewed in the second stage of this work, though coinciding to a great extent in their opinions, clearly based these opinions on intuition and personal experience rather than existing formal data. As a result, is was not possible to carry out sector-by-sector analysis in sufficient detail for the diagnosis to serve as a basis for the design of specific development actions in these sectors; the results of using geographical information systems and other analytical tools are only as good as the data with which they are fed (Rodríguez et al., 1999). The diagnoses of individual sectors are therefore no more than a rough description of their general situation. What can be stated with absolute certainty is the global conclusion that, as an essential first step towards precise planning of specific development actions, it is necessary to develop mechanisms for provision of the information that are lacking. More specifically, the global diagnosis of the planning situation is as follows.

1- Information on Huetar Norte is currently insufficient in quantity, quality, geographical coverage, sectorial detail and systematic integration.

2- The sustained collection of sufficient systematic information is essential, and to this end a general system for the collection and organization of regional data must be designed and put into practice with the coordinated collaboration of all the public and private organizations concerned with the development of the region.

3- Once such a Regional Information System (RIS) has been established and appropriate inventories have been carried out, it will be possible to carry out proper diagnosis and planning activity and to monitor the results of the implementation of plans issuing therefrom.

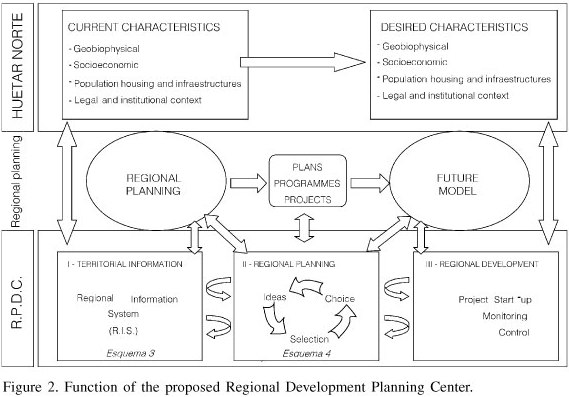

Action Proposal

In view of the above, it is proposed that the UNESCO Chair be incorporated in an eventually self-supporting Regional Development Planning Center (RDPC) with capacity not only for teaching and research on rural development, but also for the development, establishment and maintenance of the RIS described above; for analysis of the information gathered and formulation of a model of the region as the ultimate development goal; and for the design, proposal and follow-up of specific development actions aimed at achieving this goal (Figure 2). The UNESCO Chair should contribute to these efforts not only directly but also indirectly by facilitating access to the experience of other countries at both academic and governmental levels (Cancela et al., 2001) as regards the follow-up of development programmes in the European Union.

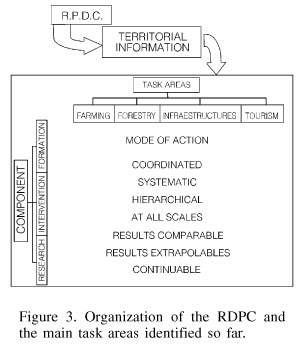

The organization of the RDPC

The proposed RDPC is envisaged as consisting of three operational units that, though acting jointly in pursuit of the established objectives, will have as their separate primary concerns a) teaching and training in fields in which the developmental needs of the region demand expertise, b) research, with strong emphasis on the needs and situation of Huetar Norte, and c) planning and development actions. These operational units will collaborate in regard to all the sectors and fields mentioned in this paper (farming, forestry, tourism, infrastructures and, last but not least, the RIS), together with others that may emerge as sectors of interest in the course of on-going analysis (Figure 3).

Teaching and training. The Teaching and Training Unit will aim to reinforce the skills of the workforce by giving training in relevant areas at levels ranging from post-graduate tuition (PhD and Masters courses) to basic grass roots instruction. The possibility of exchanging teachers and students with foreign centres should be evaluated in due course.

R+D. The Research Unit should concentrate on applications-oriented research in the sectors of greatest socioeconomic importance and/or possibilities of growth, and concern both production (in a broad sense including the conservation of landscapes and natural resources of value to the tourist industry, for example) and the quality of life of the population (for example, as regards housing, communications, etc.).

Intervention. The Teaching and Training and R+D Units are typical of the activities of UNESCO Chairs. The Intervention Unit is not academic in character, its activities being more proper to a government agency, but its creation and operation are regarded as essential for the success of those other units, and the need for close coordination of the efforts of all three make their inclusion in a single center highly desirable. As well as gathering and analysing regional data, the Intervention Unit will use this data for rational planning of specific actions, which it will propose to the relevant bodies, and will monitor and facilitate the progress of such actions. Its remit will also include the procurement of finance for the RDPC in return for services provided to companies and other organizations involved in the initiatives it promotes (e.g. tourist accommodation companies or forestry companies interested in primary and secondary transformation of timber).

Each of the above three units will contribute in its own way to the problem areas and sectors identified by the Center. Initially, on the basis of the tentative diagnosis that that has been arrived at so far, these are as follows.

Information. Of the five areas of intervention so far identified, this is the only one which it is possible at this time to discuss in any detail. It is therefore dealt with separately below as a Regional Information System.

Farming and Food Processing. As the most important economic sector of Huetar Norte, the food industry should lead the development of the region. It should increasingly be oriented towards local food processing rather than export to foreign processors. The design and execution of rigorous agricultural censuses will provide a basis for rational region-wide short- and medium-term crop planning and quality regulation schemes, and will contribute to facilitating communication between producers and appropriate markets.

Forestry. Next to farming, forestry is in macroeconomic terms the main source of wealth in Huetar Norte. Accurate systematic monitoring of variations in woodland surface areas, timber stands, etc., is especially important in this industry given the time scale of its production process. Forest inventories should be carried out systematically with a periodicity appropriate for the average growth rate of the major timber species, and be used to create and update vegetation maps that can be used for planning production and forest care services.

Tourism. As regards new economic activities, Huetar Norte has placed its hopes in tourism. This sector has grown rapidly in recent years, and there is an urgent need of coordination mechanisms that place all the current supply of attractions and accommodation at the tourists disposal while allowing research into the viability of new proposals and alternative forms of exploitation that are currently being experimented with in other countries. The RDPC should play a major role in providing personnel, methodology and information services in this field on an integrated, region-wide basis.

Infrastructure. As noted in previous sections, all the various kinds of infrastructure of the region are deficient in quantity and quality. Good infrastructures are essential for regional development, and one of the RDPCs main tasks will be an appraisal of the situation in this field and the design of remedial measures in the light of the requirements of the major economic sectors.

The Regional Information System

As stressed at various points in this paper, the first task before the RDPC will be the establishment of a data base and of the mechanisms for its continuous updating, maintenance and use. Without this, there will be no sound basis for tackling any of the other tasks mentioned above.

The initial establishment of the Regional Information System will involve

- Identification, inventory and classification of existing data sources (government agencies, NGOs, and others);

- Analysis of current data collection systems so as to obtain a detailed diagnosis of strengths and weaknesses;

- Design and establishment of a systematic, integrated data collection system allowing proper dynamic diagnosis of the state of the region and on-going planning of its development.

The particular contributions of each of the three component units of the RDPC in this initial phase and/or the subsequent maintenance, use and development of the RIS may be roughly envisaged as follows.

Teaching and training. The primary tasks of the Teaching and Training Unit will be to supply students in various kinds of courses, including courses for relevant technical staff working in government or in private companies, with training in the concepts and techniques of regional analysis; to train specialists in relevant technology such as geographical information systems, inventory methodology, social science surveys, etc.; to provide education and information about the region to relevant industries and the general public (including internet services); and to organize the collaboration of visiting lecturers so as to exploit the experience of foreign universities, governments and companies in the rural development field. The RDPCs hoped-for UNESCO Chair status should facilitate the collaboration of top-ranking experts in the in situ specialist training of research students and others.

R+D. Research in this field should be carried out in collaboration with universities and other government institutions. Possible topics of interest might be the production of relevant computer programs, computer aided mapping and map publishing, interpretation of aerial photographs and remote sensing images, and the application and adaptation of census and survey techniques to the population of Huetar Norte. Specific research goals will depend on the needs identified in the course of diagnostic activity. It is expected that the opportunities for research will attract post-graduate students from other Costa Rican higher education centers and from abroad, and also that finance might be forthcoming by attracting the interest of banks and other government agencies in censuses and surveys of mutual interest.

Intervention. The actual field work involved in carrying out farming censuses, population censuses and surveys of various kinds will be the responsibility of the Intervention Unit, which will also manage the data bases so created and use it for planning purposes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The first phase of this work was carried out with the financial support of the Directorate General for External Affairs of the Xunta de Galicia (Spain).

REFERENCES

1. Cancela J, Crecente R, Álvarez C (2001) Modelo para la evaluación de programas de desarrollo rural en la Unión Europea. Información Tecnológica 12: 155-162. [ Links ]

2. Colburn FD (1993) Exceptions to urban bias in Latin America - Cuba and Costa Rica. J. Dev. Studies 29: 60-78. [ Links ]

3. Crecente R, Álvarez C, Fra U (2002) Economic, social and environmental impact of land consolidation in Galicia. Land Use Policy 19: 135-147. [ Links ]

4. De Janvry A, Sadoulet E (2000) Rural poverty in Latin America Determinants and exit paths. Food Policy 25: 389-409. [ Links ]

5. Fallas Venegas H (1993) Costa Rica: Situación Actual y perspectivas del desarrollo rural. Serie Política Económica Nº6. EUNA. Heredia, Costa Rica. 66 pp. [ Links ]

6. Fernández A, Rosales MCh, Hernández EZ (1999) Políticas Agrícolas y cambio institucional para el desarrollo regional y rural. EUNA. Heredia, Costa Rica. 138 pp. [ Links ]

7. Holl KD, Loik ME, Lin EHV, Samuels IA (2000) Tropical montane forest restoration in Costa Rica: Overcoming barriers to dispersal and establishment. Restoration Ecol. 8: 339-349. [ Links ]

8. Hyde WF, Kohlin G (2000) Social forestry reconsidered. Silva Fennica 34: 285-314. [ Links ]

9. Knickel K, Renting H (2000) Methodological and conceptual issues in the study of multifunctionality and rural development. Sociologia Ruralis. 40: 512-519. [ Links ]

10. Korzeniewicz RP, Smith WC (2000) Poverty, inequality, and growth in Latin America: Searching for the high road to globalization. Lat. Amer. Res. Rev. Nº35: 7-54. [ Links ]

11. Marcouiller DW, Clendenning JG, Kedzior R (2002) Natural amenity-led development and rural planning. J. Planning Litt. 16: 515-539. [ Links ]

12. MIDEPLAN (1996) Principales indicadores ambientales de Costa Rica. MIDEPLAN/SIDES. San José, Costa Rica. 122 pp. [ Links ]

13. MIDEPLAN (1997) Principales indicadores sociales de Costa Rica Nº2. Ministerio de Planificación Nacional y Política Económica. San José, Costa Rica. 347 pp. [ Links ]

14. MIDEPLAN (1998) Estado de la Nación, Nº4. Ministerio de Planificación Nacional y Política Económica. San José, Costa Rica. 527 pp. [ Links ]

15. Murdoch J (2000) Networks - a new paradigm of rural development? J. Rural Studies 16: 407-419. [ Links ]

16. North LL, Cameron JD (2000) Grassroots-based rural development strategies: Ecuador in comparative perspective. World Development 28: 1751-1766. [ Links ]

17. Pérez Sáinz JP (1999) Mejor cercanos que lejanos. Globalización de Empleo y Territorialidad en Centroamérica. FLACSO. Guatemala. 196 pp. [ Links ]

18. Reinhardt N, Peres W (2000) Latin Americas new economic model: Micro responses and economic restructuring. World Development 28: 1543-1566. [ Links ]

19. Rodríguez JR, Crecente R, Álvarez C (1999) Metodología para el estudio del sistema territorial mediante sistemas de información geográfica (SIG). Información Tecnológica. 10: 181-188. [ Links ]

20. Steiner K, Herweg K, Dumanski J (2000) Practical and cost-effective indicators and procedures for monitoring the impacts of rural development projects on land quality and sustainable land management. Agricult. Ecosyst. Environ. 81: 147-154. [ Links ]

21. Tourino J, Parapar J, Doallo R, Boullon M, Rivera FF, Bruguera JD, González XP, Crecente R, Álvarez C (2003) A GIS-embedded system to support land consolidation plans in Galicia. Int. J. Geog. Informat. Sci. 17: 377-396. [ Links ]

22. Van der Ploeg JD (2000) Revitalizing agriculture: Farming economically as starting ground for rural development. Sociologia Ruralis 40: 497-506. [ Links ]

23. Van der Ploeg JD, Renting H (2000) Impact and potential: A comparative review of European rural development practices. Sociologia Ruralis 40: 529-536. [ Links ]

uBio

uBio