INTRODUCTION

Early Studies and Statistics from British Council (2023) and Education First (EF, 2023) indicate that Ecuador has one of the lowest levels of English proficiency among Spanish-speaking countries in South America (Ecuavisa, 2023). This disparity creates significant challenges for the educational and professional development of the country. The causes of this disparity are diverse and include traditional teaching methodologies, lack of resources in public schools, poor teacher training, low rates of bilingualism in the population, and socioeconomic and cultural factors. One of the consequences is the difficulty Ecuadorian students have in communicating orally in English, which limits their participation in different academic, professional, and social contexts (Ullauri-Moreno, 2017).

Despite this situation, there is a growing interest in teaching strategies that can effectively address the challenges of teaching English in Ecuador. Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) is one of the strategies that has received particular attention in the educational literature. CLIL refers to a pedagogical approach that integrates the learning of a foreign language with the acquisition of academic or disciplinary content, providing students with opportunities to develop language skills in an authentic and meaningful context (Delliou & Zafiri, 2016a).

This research aims to explore the benefits of implementing CLIL in an Ecuadorian university focusing on the improvement of undergraduate students' oral communication skills in English. It is expected that by using CLIL in instruction, students will not only develop their English language competencies, but also acquire knowledge and skills in their academic or disciplinary field. This combination of approaches could enhance students' motivation and engagement in learning a second language, as well as an increase in their communicative competence in the academic and professional context, providing empirical evidence on the most effective strategies to develop speaking abilities.

This study will be conducted at an Ecuadorian university, where a CLIL pilot program will be implemented. Participating students will be assessed before and after the intervention to measure their progress in English oral communication skills. The results of this study are expected to provide valuable information on the benefits of CLIL implementation in the Ecuadorian university context, and contribute to the growing evidence based on the effectiveness of this teaching strategy at the moment of improving students' speaking competencies.

Further analysis of this topic is important because it can affect different academic situations such as the access to scholarships, exchange programs, and even the admission to higher education abroad, instead of limiting the comprehension of academic texts and the participation in classes and activities due to lack of language mastering.

LITERATURE REVIEW

CLIL, the acronym for Content and Language Integrated Learning, is a pedagogical approach that combines the learning of a foreign language with the acquisition of knowledge in other curricular areas (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010). This approach offers a wide range of applications as it can be used for any learning content and will greatly promote the use of English, as well as a varied and practical perspective on the use of languages for knowledge acquisition.

According to Coyle, Hood and Marsh (2010), CLIL use a variety of tools that allow students to communicate and enrich their oral skills. Students will have different opportunities to see language as a learning tool, which will allow them to think outside the box and look at information from different perspectives, as they will have better thinking skills and cognitive development. It also allows learners to get more about their culture and other cultures for a better global understanding.

CLIL can be analyzed from different categories, reflecting its complexity and its potential to improve learning. One perspective place it within the pedagogy of the communicative approach, where communication becomes the main objective of foreign language learning (Ellis, 2003). This approach emphasizes the use of language in real and meaningful contexts.

On the other hand, authors such as Dörnyei (2009) situate CLIL within the psychology of language learning, focusing on the cognitive and affective processes involved in language learning in a content context. They emphasize the importance of motivation, self-esteem and confidence in learners' ability to learn.

Furthermore, CLIL can also be analyzed from the perspective of sociolinguistics, which studies the relationship between language and society, exploring how language use in CLIL impacts on cultural identity and social interaction (Lorenzo, 2007). Finally, foreign language didactics contribute to the analysis by providing tools and methodologies for the effective implementation of CLIL in the classroom (Fajardo et al., 2020).

CLIL is of utmost importance when teaching a second language, especially when learners need to start a conversation, since it encourages creativity and competitiveness to develop the necessary linguistic skills when speaking about common topics. CLIL can develop this ability by focusing on communication and interaction. It helps to understand the language, to interact, to develop techniques for a better speech, and to improve communication. It is important to mention that students with basic vocabulary will show poor performance, however CLIL also contributes with memory strategies that can be used to keep new words (Aladini & Jalambo, 2021). CLIL is also a synonym of awareness and cultural opportunities for students when learning a second language. In the process of mastering the ability to speak, the new language is applied in different social contexts. CLIL encourages learning through different tools like books, audios, authentic resources to develop conversations among students that leads to an organically integration, without forcing it. Finally, in CLIL, fluency is prioritized over correction, considering errors as a natural part of the language learning process. Students develop fluency in English by communicating for different purposes, allowing them to expand their linguistic resources and respond to the content they are learning (Novitasari et al., 2021).

In a globalized world, the mastery of English as a lingua franca has become a fundamental tool for professional and personal success. The ability to communicate orally in English opens up endless possibilities in various areas of life. Professionally, English is the language of international business, conferences and academic publications. Mastering it allows access to better jobs (British Council, 2023), participating in international projects and collaborating with professionals around the world (Coyle, Hood & Marsh, 2010), presenting ideas and projects with confidence in international meetings and conferences (Pinoargote-Cedeño, 2019), negotiating business agreements effectively (Guamán-Gutama, 2018) and serving international clients by providing them with quality service (Ullauri-Moreno, 2017).

From a personal perspective, English allows to travel the world and communicate with people from different cultures (British Council, 2023), access a wider variety of information and entertainment (Coyle, Hood & Marsh, 2010), improve cognitive skills, memory and the ability to concentrate (Pinoargote-Cedeño, 2019), develop self-confidence and self-esteem (Guamán Gutama, 2018), and expand opportunities for learning and personal growth (Ullauri Moreno, 2017).

In addition, according to the National English Curriculum Guidelines in Ecuador (2013), A2 students in the speaking sphere should:

Give short, basic descriptions and sequencing of everyday events and activities within the personal, educational, public and vocational domains (e.g. their environment, present or most recent job, etc.).

Deal with common aspects of everyday living within the personal, educational, public and vocational domains without undue effort: Exchanging views and expressing attitudes concerning matters of common interest (e.g. social life, environment, occupational activities and interests, everyday goods and services) as well as briefly giving reasons and explanations for opinions.

Within the corresponding domains, deliver very short, rehearsed announcements of predictable, learned content which are intelligible to listeners who are prepared to concentrate.

Understand clear, standard speech on familiar matters within the personal, educational, public, and vocational domains, provided they can ask for repetition or reformulation from time to time.

Describe plans and arrangements, habits and routines, past activities, and experiences within the personal, educational, public, and vocational domains (p.19).

METHODOLOGY

This study aimed to test how the Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) approach influences the improvement of oral skills. The sample consisted of 25 undergraduate students enrolled in a Bachelor's degree programme in English at a state university in Ecuador. Their ages ranged from 19 to 23, and this research focused on measuring how their oral production evolved during the second semester of their undergraduate studies. The variable “gender” was excluded in this case since the focus relied on measuring whether there was an improvement in learners oral production when CLIL was applied. The total population of the English Development A2 evening course was taken, and their level of English in Speaking varied between A1.1 and A2.1 according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). The second-semester objective is that students achieve the A2 level in all skills by the end of the course. According to CEFR, in Speaking, A2.2 learners should "socialise in basic yet effective terms by expressing opinions and attitudes in a simple way" (Council of Europe, 2003, p. 15).

Some extra information to be acknowledged about the characteristics of the population chosen is that many of these students entered the program with a level of A1 according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) (Instituto Cervantes, 2023). This low level of English resulted in some students withdrawing from the programme, once again highlighting the national challenge of improving English language skills. Despite government investment in English language development, as outlined in the National Multi-Year Plan 2017-2021 (Plan Nacional Plurianual 2017-2021) by the National Secretariat for Planning and Development (Secretaría Nacional de Planificación y Desarrollo, 2017), progress at the national level has been slow.

Most university students in Milagro come from lower-class households (INEC, 2022), which limits their access to external English classes such as COPEI and CEN, as they cost approximately $150 per month (COPEI, 2023; CEN, 2023). These values, along with transportation to Guayaquil ($1,25 per trip) and other expenses, exceed the living wage of $460 (Ministerio de trabajo, 2023), creating a significant economic burden for families (Burbano & López, 2023). Considering that statistically and in practice the leading socioeconomic level in Ecuador is "vulnerable and impoverished representing 66.6% of the population", that is, "people that live with a monthly income of less than USD 210.13" (Mora, 2021), this worsens and hinders the possibility for a regular student to access language education beyond public education.

Lack of employment, cultural, economic, racial factors, and nepotism are some of the obstacles that Ecuadorian households face in accessing higher education. This perception influence in many young people who seek short or technical careers after high school, undervaluing the acquisition of languages. When these young people graduate from high school and decide to enter university, the low foreign language level impedes them to advance in an optimal way (Burbano & López, 2023).

STUDY DESIGN

The study follows a quasi-experimental design, a pre-test and a post-test were applied. The quasi-experimentation design was chosen as it refers to situations in which researchers cannot randomly assign participants to different experimental conditions, but still conduct measurements before and after an intervention (Rogers, 2020). The independent variable is the CLIL approach meanwhile the dependent variables are the use of vocabulary, time management, fluency, and confidence, common criteria to measure how proficient a learner could be when speaking.

The pre-test was applied at the beginning of the semester as a diagnostic assessment in order to measure the students’ oral skills in terms of vocabulary, time management, fluency and confidence. These dimensions, measured together, allow for a more holistic assessment of oral communication skills, helping to identify areas of strength and opportunities for improvement in a student's communication performance (Shteiwi & Hamuda, 2016). Vocabulary is essential for expressing ideas accurately and comprehensibly. The ability to use a diverse and appropriate vocabulary indicates not only language knowledge but also the ability to select and apply words effectively in a specific context. Time is a valuable resource in oral communication. Effective time management demonstrates the ability to organise and structure information efficiently. Fluency includes aspects such as speed, absence of unnecessary interruptions and consistency of delivery that facilitates understanding and connection with the audience. Finally, confidence in oral communication influences the audience's perception of the speaker (Rahmawati & Ertin, 2014).

For the pre-test, students were given specific topics selected by the teacher according to their level A2 and they presented in a typical way, using a PowerPoint presentation and trying to remember what they had memorized. This will be further explained during the results discussion.

As a way to improve students' performance, CLIL was introduced for the next presentations as this approach offers effective activities to improve students' oral production in a foreign language (Delliou & Zafiri, 2016b). Rather than focusing exclusively on grammar and vocabulary (classical format), the activities included debates, role-plays, small group discussions of authentic texts and even competitions similar to “Who Wants to be Billionaire”. These activities encouraged effective communication, providing a meaningful context that facilitated the retention and application of new words. Furthermore, it challenges students to organise their ideas within time limits and contributed to developing fluency as they chose topics of their interest related to the course book units that helped to strengthen their confidence to express themselves effectively in the foreign language.

During the post-test, students showed substantial improvement when compared to the pre-test performance.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

As it was stated in the previous section, there was a pre-test and a post-test to prove if CLIL helps to improve oral communication in foreign languages students. The following data was obtained.

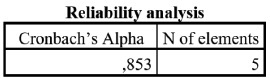

As this is a quasi-experimental study, where random assignment is not feasible, reliability analysis is crucial to assess the consistency and coherence of the measures used to avoid erroneous conclusions about the effects of the intervention, compromising the robustness of the findings (Mays, 2019). The Cronbach’s Alpha result of 0,853, higher than 0,70 ensures that measurements were reliable and accurately reflected changes in the dependent variables use of vocabulary, time management, fluency, and confidence.

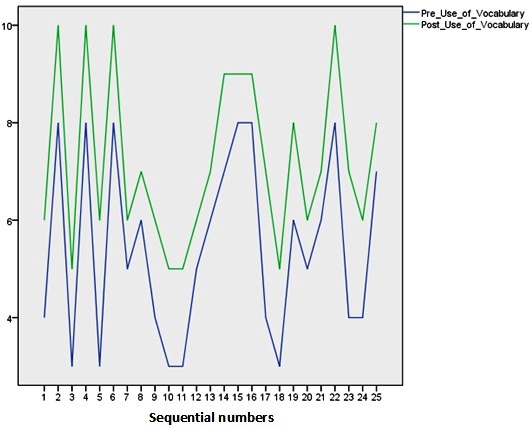

Figure 2 shows a meaningful difference between the pre-test and post-test in terms of use of vocabulary. It was proved that the CLIL approach significantly enhanced students' vocabulary by providing an authentic and meaningful context for new words acquisition. The thematic content learning allowed students to immerse themselves in an environment where ideas become practical. Specific vocabulary related to the learning topics was also used naturally during the activities (discussions, debates, role-plays), facilitating their assimilation. In addition, repetition and constant application of these words in a variety of situations strengthen retention and understanding. This intrinsic connection enabled learners to use vocabulary more accurately and functionally in real-life contexts.

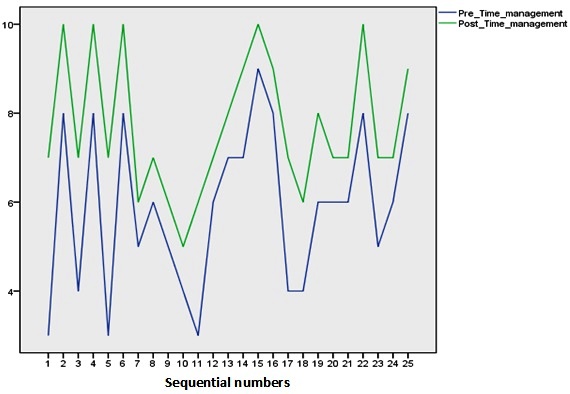

Figure 3 demonstrates that time management improved in post-test when compared to pre-test. CLIL engages students in tasks that demand time efficiency. Presentations in a CLIL context often require students to communicate relevant information within specific time limits. This challenge encourages effective planning and organisation of discourse. Students learn to structure their presentations coherently and to allocate time appropriately to each section. This practical approach not only benefits oral communication, but also prepares students for future situations where effective time management is essential, providing them with valuable skills for their academic and professional development.

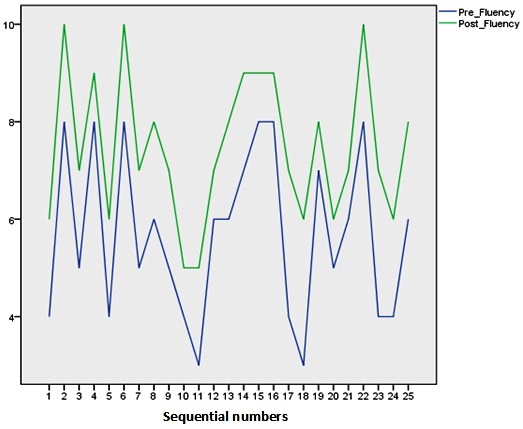

Figure 4 illustrates how fluency evolved from the pre-test to the post-test. During CLIL presentations, students are immersed in discourse on specific relevant and preferred topics, encouraging fluent expression of related ideas and concepts. The intrinsic connection between content and language facilitates natural and coherent communication, allowing fluency to develop organically. In addition, the constant practice of communication in an authentic environment contributes to overcoming barriers of hesitation and enhances the ability to express oneself clearly and without interruption.

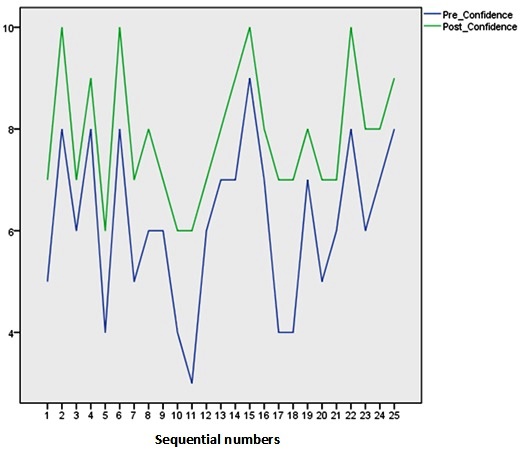

Figure 5 confirms that confidence increased from pre-test presentations to post-test ones. CLIL plays a key role in improving students' confidence by allowing students to present information on topics of their interest and relevance. This authentic and meaningful context strengthens the emotional connection to the content, which leads to greater confidence in expressing ideas and opinions in public. The constant practice of presentations in a CLIL environment, where students practically apply language, reduces communicative anxiety and fosters confidence in oral communication.

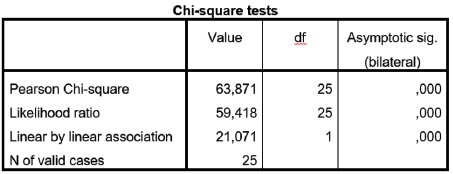

Pearson Chi-square value, as a measure of the discrepancy between the observed and expected frequencies of the data, is 63.871 with 25 degrees of freedom. The associated p-value (asymptotic significance) is 0.000, which is less than the conventional significance level of 0.05. This indicates that there is a statistically significant association between the variables. In the same way, the likelihood ratio chi-square value is 59.418, also with 25 degrees of freedom, and a p-value of 0.000, confirming the statistical significance. Finally, the linear-by-linear association chi-square value is 21.071 with 1 degree of freedom and a p-value of 0.000 highlights the significant linear trend in the association of the variables chosen (Cresswell, 2014).

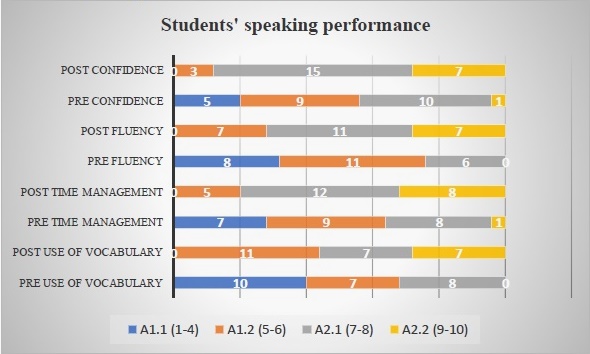

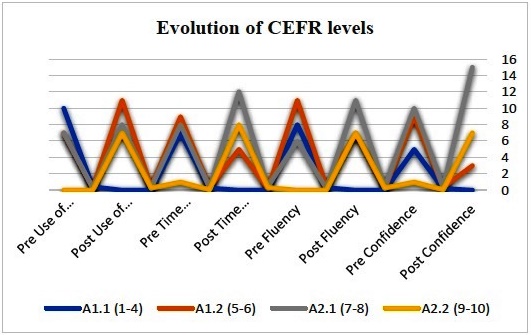

Figure 7 validates the alternative hypothesis of this study. It states that CLIL helps students to boost their oral skills. In the pre-test 40% of the class belonged to A1.1 level in terms of use of vocabulary, 28% had some problems managing time properly, 32% struggled with fluency, and 20% showed a lack of confidence when presenting. In the post-test, these numbers changed and most of students improved in all the variables reaching the A2.1 level. 32% showed a correct use of vocabulary, 48% had better time management, 44% had progress in fluency and 60% developed confidence when presenting.

Figure 8 shows the class's overall performance. It can be seen that at the beginning of the semester, in terms of speaking, level A1.1 was higher and it decreased by the end. Level A1.2 also diminished across the time. Level A2.1 displays a higher increase which makes sense as on average students reached the level expected for the second semester. Finally, Level A2.2 also improved but at a lower speed.

CONCLUSIONS

The study confirms the effectiveness of CLIL as a strategy for improving oral communication in English among university students in Ecuador. The results, based on a quantitative and qualitative analysis of data, demonstrate a positive impact on the variables assessed.

For the use of vocabulary, a significant increase was observed in the richness and accuracy of the vocabulary used by students in their oral presentations (Coyle, Hood & Marsh, 2010). This is due to exposure to authentic and contextualised language in CLIL activities (Delliou & Zafiri, 2016). In terms of time management, students improved in organising and managing time during their presentations. The practice of structuring and timing their presentations in CLIL provided them with tools to optimise the use of time (Rogers, 2020). In the case of fluency, the constant interaction in CLIL activities allowed them to develop greater spontaneity when expressing themselves (Rahmawati & Ertin, 2014). Finally, participation in CLIL activities led to an increase in self-confidence and communication skills. Students were more motivated and willing to participate in oral communication situations in English (Pinoargote-Cedeño, 2019).

Furthermore, this research brings empirical evidence to the Ecuadorian context, where low English proficiency represents a challenge. The study contributes to the growing database on the effectiveness of CLIL in different contexts and populations, strengthening the literature on this pedagogical approach (British Council, 2023; Dörnyei, 2009). Implementing CLIL in English language teaching in Ecuadorian universities, especially in the development of oral communication skills needs special training for teachers in the CLIL approach to ensure effective implementation. This training should be contextualised and practical, so that teachers can adapt CLIL to their needs and those of their students (Instituto Cervantes, 2023).

Further research is needed to explore the implementation of CLIL in populations with different characteristics, such as level of English, learning styles, motivation and access to resources (Burbano & López, 2023). Also, to develop specific assessment instruments that consider the complexity of oral communication and the contextualised nature of learning in CLIL as well as the strategies required to promote the adoption of CLIL at institutional and national levels, including investment in teacher training and the development of appropriate teaching material.